Emanuel Ninger walks into a bar. It’s a chilly Saturday afternoon in New York, March 28, 1896. He has come to town on business from his Flagtown, New Jersey, home fifty miles west of the city. He owns a small farm there, but he mainly gets by on a Prussian army pension and some modest investments. So he tells his neighbors.

His last stop that day is at a Cortlandt Street tavern, where he orders a glass of Rhine wine. The dapper, bearded man smokes a cigar and speaks amiably in a German accent with the bartender. He pays and, on his way out, asks the proprietor if he can change a fifty-dollar bill—he has to pay some farm hands on Monday. They make the exchange and Ninger goes on his way.

A minute later, the bartender shouts for his assistant to run after the man— they’ve been cheated! The assistant can’t spot the customer in the street but on a hunch sprints toward the Hudson River ferry landing. He alerts a policeman along the way. They grab Ninger before he can board the vessel. The arrest ends the fourteen-year career of a truly unique criminal.

America had always been rife with counterfeiters—some were British “coney men” transported to the colonies for their misdeeds. Benjamin Franklin, a printer by trade, worked with several colonial governments to try to thwart illicit currency as early as the 1730s. The nineteenth century saw so much counterfeiting that by the Civil War an estimated one-third of all banknotes were bogus. The federal government established the Secret Service in 1865 to combat the crime wave.

Ninger, forty-nine years old, was in fact a sign painter who had come over from Prussia with his wife and four children in 1882. In this land of opportunity, he decided to make money—literally. He bought high quality bond paper, cut it to size, and soaked each sheet in weak coffee to give it a used feel. While it was still wet, he positioned it atop a genuine note on a pane of glass lit from below.

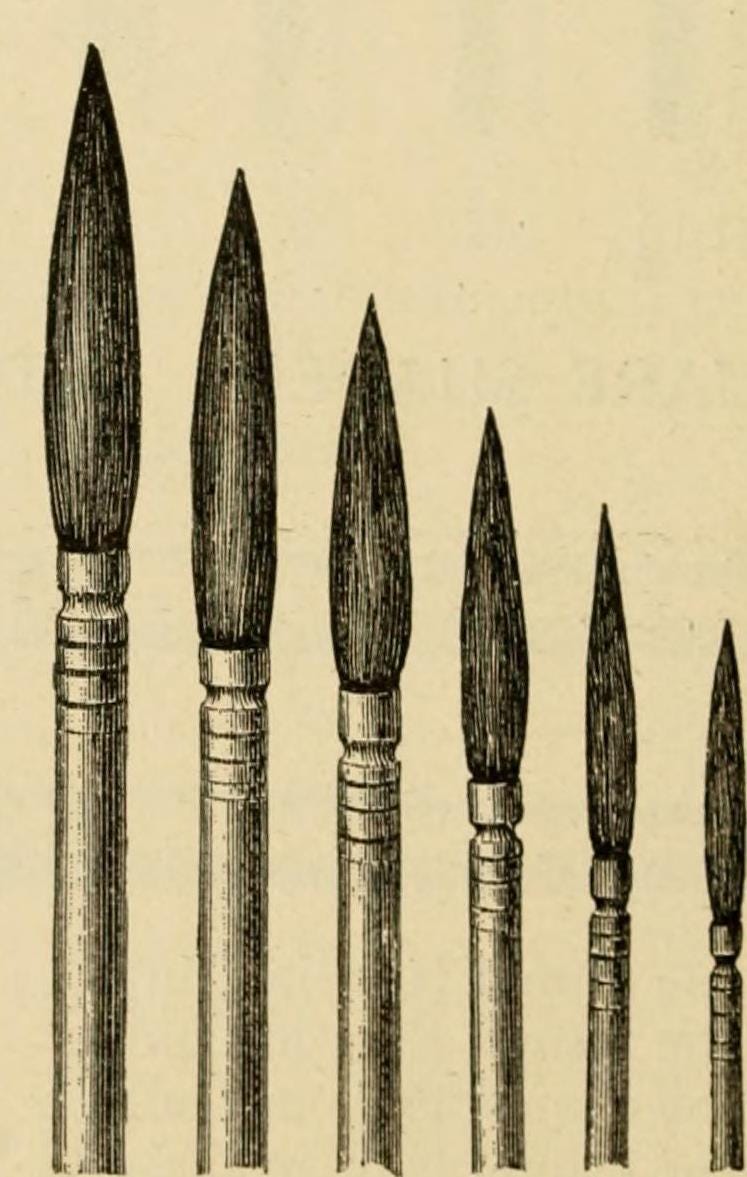

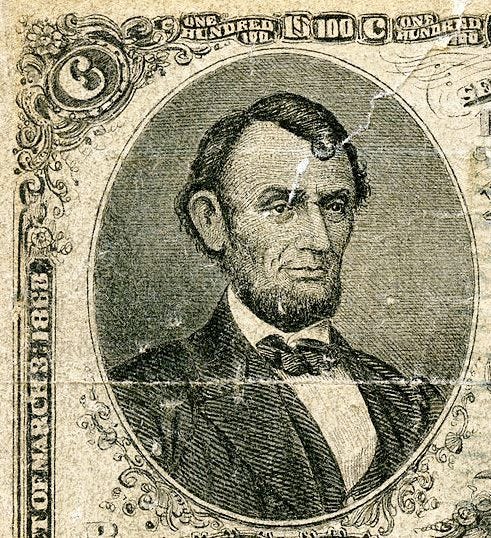

Next he carefully traced the outlines of the bill’s design with a hard lead pencil. When the counterfeit dried, he went over it with ink, copying every detail with a pen and an exceedingly fine camel-hair brush. He even replicated the red and blue threads worked into actual banknote paper. The government had introduced intricate machine-generated engraving techniques to make the bills harder to copy. Ninger possessed a special gift for giving the impression that his own bills had similar detail, although a close examination revealed it was an illusion.

The artist worked hard on each facsimile, spending many hours every week copying a single banknote. The effort paid off—twenty dollars then was worth six hundred in today’s currency; a converted hundred gave the artist the equivalent of three thousand dollars. He protected himself by maintaining a one-man operation. He discreetly passed the bills himself, usually in Manhattan liquor stores, often on Friday or Saturday when merchants were prepared to cash paychecks.

Ninger-produced bills had been turning up for years, frustrating the police and Secret Service agents. So convincing were they that they had usually passed through several hands before being discovered, making it impossible to trace them to their source. Some merchants, recognizing that the hand-drawn copies were works of art, framed and even sold them.

Ninger’s downfall came when the bill he passed in the tavern was placed on a wet counter. Printers used permanent oil-based ink; Ninger drew his notes with ordinary water-soluble writing ink. The bartender noticed that dampness caused the note to blur and immediately realized he’d been taken.

Experts were astounded at the accuracy of Ninger’s copies. A handwriting analyst said the reproductions were “little short of genius” for which collectors would pay more than face value. “I will gladly contribute it to a fund to defend the artist,” he concluded.

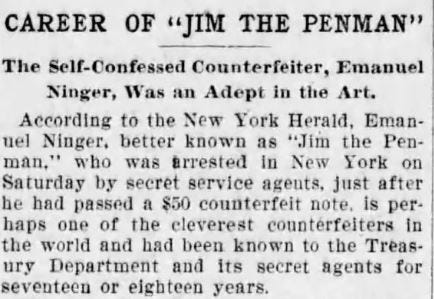

Ninger became an overnight legend—newspapers dubbed him “Jim the Penman.” He had taken on the might and brainpower of the United States government and earned his living for more than a decade, raising a family, living modestly, and contributing to charities in his community.

The artist was given a relatively lenient sentence of fifty months in prison. On release, he settled in Pennsylvania and actually did some farming. He died in 1924 at the age of seventy-seven.

Many observers pointed out that Ninger, if he had limited his draftsmanship to legal pursuits, could have earned twice as much with no risk. Maybe risk was the whole point. Maybe there was a special satisfaction in turning his labor so directly into money. Or maybe he enjoyed poking a hole in the fiction that lies at the foundation of all finance: the childlike make-believe that declares pieces of paper to be worth vast sums.

Today, since counterfeit bills are illegal no matter how old their prototype, Ninger’s handiwork is still subject to confiscation by authorities. Although the bills that have survived have purportedly been sold for hefty sums, the transactions are, of necessity, secret.

Once again, a beautifully written piece about an obscure and interesting subject. Thanks, Jack!

Another great historical momento told with a touch of compassion and humor.

Thank you