America’s bankers have a remarkable ability to grin in the face of adversity. Reassurances have been laid on thick in the wake of the recent collapse of First Republic Bank. Hey, it was only the second largest bank failure in the nation’s history. And the third and fourth largest failures were almost two months ago. Don’t sweat the small stuff, man.

The situation has echoes of events back in 1893. Then, the role of Silicon Valley was played by the railroads, the prototype of bloated industrial corporations. After a track-laying frenzy following the Civil War, many of these companies were drowning in debt; a few had already gone under. Investors on Wall Street, one observer noted, were “pissing down their legs.”

In fact, the national economy was in free-fall, heading toward a depression such as Americans had never seen before. Some of the biggest banks and most established brokerage firms were collapsing. In early May—exactly 130 years ago—the bottom fell out. As I put it in my book The Edge of Anarchy:

The stock exchange erupted. “The floor might have passed for a morning in Bedlam,” an observer noted.

All day, brokers swung from “wildest excitement” to lulls when they seemed to sink into apathy. Then, hearing a rumor, spotting an opportunity, fearing the worst, they again sprang into a frenzy, pushing their fellows out of the way to grab at a trade.

One broker said it was the worst day he had ever seen. “While there may be a God in Israel,” he stated, “we need him on Wall Street.” Forced optimism prevailed—the panic may have been a blip. But traders would wait in vain for Jehovah to visit the stock exchange. May 5, 1893, was only the beginning.

The causes of the national calamity were complex and ultimately mysterious. Economists, who had been offering bland reassurances for months, were blindsided. Nervous European bankers and governments rushed to redeem American notes for gold. U.S. reserves of the precious metal evaporated. American banks, equally spooked, stopped making loans. Depositors, fearing the loss of their funds, rushed to convert their accounts to cash. Consumer spending dried up.

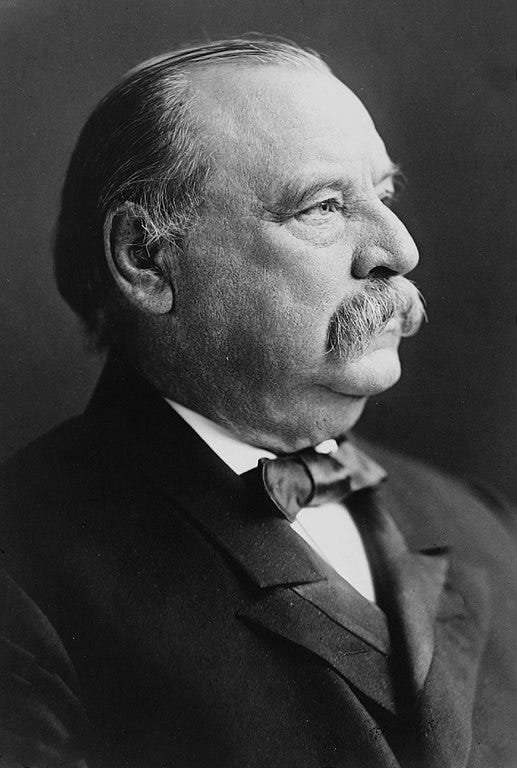

A mind more subtle than President Grover Cleveland’s would have been hard pressed to identify all the forces that were coming together to accelerate the downturn. Overinvestment in railroads, the manipulation of tariffs, and sheer psychology—it all played a role. Nervous denizens of Wall Street pressed Cleveland to do something. Anything.

The president, like many Americans, believed in the mystique of precious metals, the gospel of the gold standard. He called a special session of Congress to repeal the Silver Purchase Act, which had obligated the government to buy and mint American silver. Cleveland thought that cheap money was debasing the currency.

His silver solution didn’t work. Joblessness climbed to unprecedented levels across the country. A New York City street preacher said “one could hear human virtues cracking and crumbling all around.” In Boston, historian Henry Adams observed that “everyone is in a blue fit of terror, and each individual thinks himself more ruined than his neighbors.” Five thousand Polish immigrants in East Buffalo, New York, were reported in “imminent danger of starvation.”

The wounded economy staggered along for another eighteen months. Then, in 1895, things really got bad. As a rule, the U.S. government tried to keep its level of gold reserves above $100 million. By early that year, the Treasury had only $45 million left. A few weeks later, it was down to $9 million. A run on its assets would leave the nation bankrupt. Cleveland proposed selling $60 million in bonds to replenish the coffers. But who would buy them?

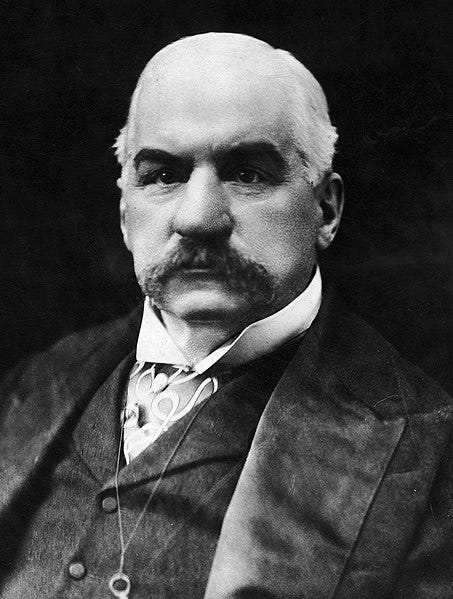

At this point, J.P. Morgan—the most formidable of the nation’s plutocrats—proposed a deal to purchase all the bonds for gold. The influx of hard money succeeded in allaying the trepidations of investors and the general public. Morgan quickly resold the bonds at higher prices, netting millions more than he had paid. The suffering of common men and women continued, but the government would remain solvent until the economy regained its feet two years later.

Coincidentally, this year’s bailout starred JPMorgan Chase, the financial behemoth built on Morgan’s original bank. Chief executive Jamie Dimon generously offered to purchase First Republic Bank for $10 billion and thereby stabilize the financial system. The company expects to turn a profit of $500 million, perhaps much more, on the deal.

So, for now, everything’s copacetic. Oh, except for the debt-ceiling impasse in Congress. But there’s a good three weeks to go before we approach that cliff. As Roy Rogers used to croon: Keep smiling until then . . .

(Read more about the wild and woolly 1890s in The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America.)

Thanks Jack. Seems we’ve become insensitive to any alarming news because we hear it all the time. If we ignore history…..