Talking to America appears weekly at jackkellyattalkingtoAmerica.substack.com. Likes, Shares and Comments help spread the word. Tell your friends. Check out previous essays in the Archive. All support is appreciated. And please subscribe—it’s free.

The decision by forty-five-year-old National Football League luminary Tom Brady to hang up his cleats—this time “for good”— brought to mind another retirement (not Brady’s first, a year ago, which he reversed a few weeks later to play one more season).

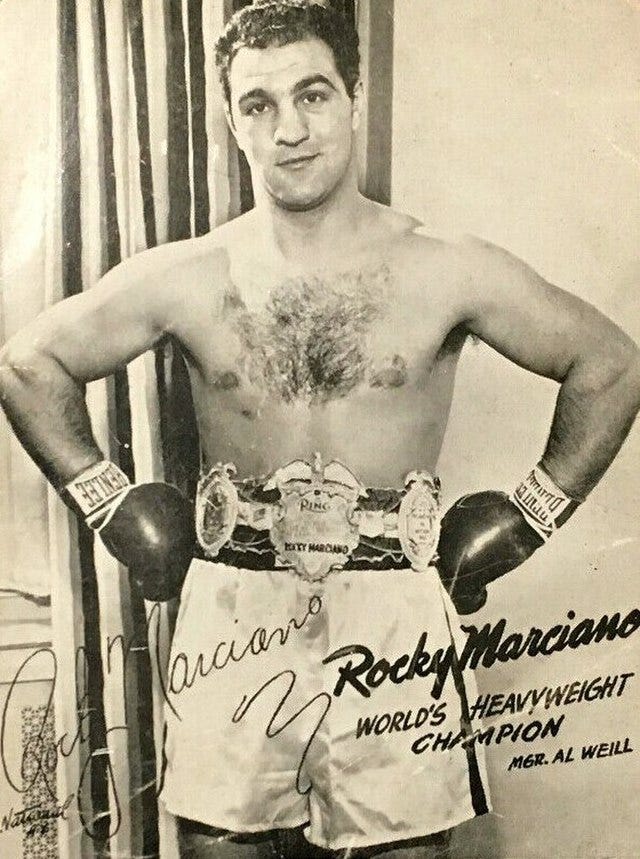

On April 27, 1956, heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano walked away from boxing at the peak of his powers, never having been beaten as a professional. He had fought 49 times and won 49 times, demolishing the best fighters of his day. He knocked out 43 of his opponents. He remains today one of very few pugilistic champions, and the only heavyweight, to have retired undefeated.

All athletes live accelerated lives. Reflexes, stamina, strength, and desire are gifts parceled unequally to the young. For a while a fighter can lean on experience and ring savvy, but eventually a competitor comes along whose youth and talents overcome the veteran’s wisdom and guile.

The saga of the athlete who refuses to acknowledge passing time is a well-worn cliché. Nor is the temptation limited to sportsmen. Frank Sinatra retired in 1971 at the age of fifty-five. He returned to the stage a couple of years later and performed in public for two more decades until he was singing off key and forgetting lyrics.

In boxing, where such hubris is nearly universal, the consequences of outwearing your welcome are more than academic. Climbing between the ropes to face punches that can maim or kill, a fighter needs a cold-eyed view of his abilities.

Growing up in Brockton, Massachusetts, Marciano had dreamed of playing major league baseball. He tried out unsuccessfully for the Chicago Cubs. After putting in a two-year stint in the army during World War II, he fought his first bout as a professional in 1947 at the age of twenty-three (Floyd Patterson, who succeeded Marciano, turned pro when he was seventeen and won the title at twenty-one).

The 184-pound Marciano was small for a heavyweight, and his boxing skills were limited. He was noted for his wild slugging and awkward footwork. But Rocky could hit. Ezzard Charles, the former champion with whom he fought two classic fights in 1954, said, “Wherever he hits you, he hurts you.”

Rocky got his title shot against Jersey Joe Walcott in 1952. Sportswriters ranked this ferocious match as one of the greatest heavyweight battles of all time. Losing on points going into the thirteenth round, Marciano hit Walcott with one short, solid punch to the chin. “To ringsiders,” a reporter wrote, “the sound of it was frightening.” Walcott toppled, Marciano was champion of the world.

Marciano’s image—devoted to his parents, clean-living and good natured—mirrored the public virtues of the Eisenhower era. The fact that he was white helped boost his appeal in a sport increasingly dominated by Black fighters. He defended his title six time over three years. His last fight was a knockout of the experienced Archie Moore in September 1955.

His mother urged him to retire while he was ahead. He had earned a respectable amount of money. There were few credible contenders left to fight. And perhaps most of all, Marciano realized that a 49-0 record would be a permanent and marketable crown to his career. He had little to gain from risking his title again, and much to lose. He quit and never boxed again.

For thirteen years after his retirement Rocky led a restless life, dabbling in business and amassing personal-appearance money, which he refused to entrust to banks. He died in the crash of a small plane in 1969, at age 46.

Back in 1951, when Marciano was a promising heavyweight but not yet champion, he faced Joe Louis in the ring. Louis had retired two years earlier. But broke and in debt, the former champ decided to attempt a comeback. As a teenager, Marciano had idolized Louis, who had established himself among the fistic immortals. But now Louis was 37, old in a sport requiring extraordinary physical acuity, and Marciano was a fresh 28.

Marciano attacked the older man with youthful energy and pure brawn. Louis resisted the onslaught with quick hands and superior boxing skills. But as the fight progressed, the crowd at New York’s Madison Square Garden began to realize that Louis was too tired, too slow, too old. In the eighth round, Marciano floored Louis twice, then knocked him out of the ring and out of boxing. When Louis came to Marciano’s dressing room to congratulate him, Rocky, perhaps catching a glimpse of the tragedy of inexorable time, wept.

Five years later, contemplating his own retirement, Rocky might have remembered that night and taken heed of sportswriter Red Smith’s comment about the fight. It was a word of caution to all athletes, including Tom Brady, who are tempted to cling to the limelight.

“An old man’s dream ended,” Smith wrote. “A young man’s vision of the future opened wide. Young men have visions, old men have dreams. But the place for old men to dream is beside the fire.”

Great stuff! Loved the short but very informative style of the author and knowledge gained on the true Rocky!