The brouhaha over U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s secret hospital stay for cancer brings to mind a medical incident from an earlier era. During the summer of 1893, the country was descending into a crisis of historic proportions. A Wall Street panic had infected the entire economy, throwing millions out of work.

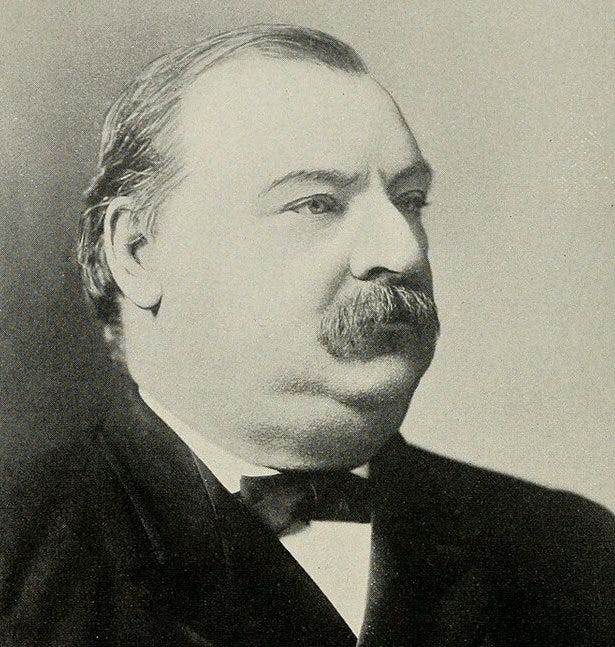

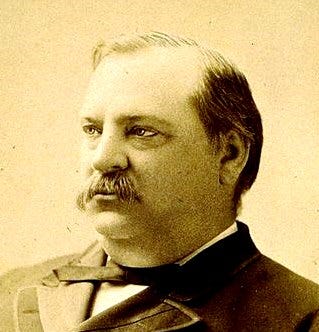

Democrat Grover Cleveland had taken office in March, the only president to serve nonconsecutive terms — he succeeded Benjamin Harrison, who had succeeded him four years earlier. Fifty-six at the time, Cleveland was a bull of a man, weighing nearly three hundred pounds. He had enjoyed one of the most meteoric political careers in U.S. history. In 1881, he was elected mayor of Buffalo, New York — four years later, he was sworn in as president of the United States. He had not gone to college and was decidedly parochial in his outlook.

Cleveland planned to address the mounting crisis by making a major change in the financial landscape. He would ask Congress to repeal the Silver Purchase Act, returning U.S. currency to a strict gold standard. Modern economists would say that the tactic was precisely the wrong thing to do during a downward spiral, but Cleveland was supported by the bankers and businessmen who advocated for hard money.

In June, Cleveland, an enthusiastic cigar smoker, noticed a rough patch on the roof of his mouth. His doctor found an ulcer the size of a quarter. A biopsy confirmed cancer. The president’s mind might have flashed to Ulysses S. Grant, another cigar aficionado, who had died eight years earlier of throat cancer.

The prospect of cancer — considered a death sentence at the time — threatened to upend his plan and to send the country into an even worse panic. The president decided to go ahead with his treatment in secret. It would not be easy for a man whose every move was covered by newspaper reporters.

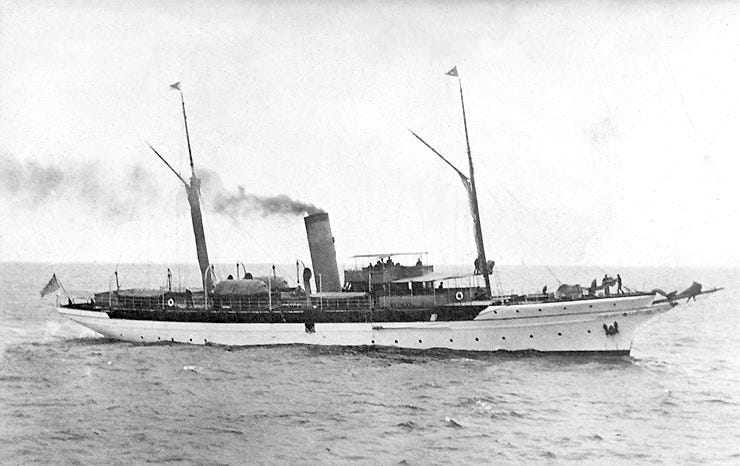

In late June, Cleveland gave out that he was on his way to his summer home in Buzzard’s Bay, Massachusetts. He took a train from Washington to New York, then boarded a luxury yacht, the Oneida, owned by a stockbroker friend. He was accompanied by a small regiment of doctors, dentists, and surgeons.

The medical team performed the operation below decks on the swaying vessel as it sailed up Long Island Sound. They propped the president in a sturdy chair tied to the main mast. A doctor injected the president’s mouth with cocaine and an anesthesiologist gave him enough laughing gas to put him out.

The dentist removed several molars to allow access. Next, the surgeon chiseled away a section of Cleveland’s upper jaw bone and removed a tumor the size of a golf ball. He was careful not to damage the patient’s eye socket in the process. When the president began to stir, the doctors gave him a blast of ether to keep him unconscious.

Cleveland was noted for his stentorian voice. With a gaping hole in the roof of his mouth, he could speak only with great effort. The press had been informed that two of his teeth had been extracted and that he was carrying on with his vacation. Cleveland confided to a friend “By God, they nearly killed me.”

A dentist made a plaster cast of Cleveland’s mouth and fashioned a rubber insert that filled the hole in his palate and restored the caved-in contour of his cheek. No scar was visible and his trademark walrus mustache remained intact — the public was fooled. A newspaper reported that he looked “in perfect health” when he returned to Washington in early August. On August 8, he delivered his message to Congress, which led to the repeal Cleveland had wanted.

The day after the legislative victory, Elisha Edwards, a journalist for the Philadelphia Press, reported the story of the maritime surgery — he had gotten the information from one of the doctors. But the other participants closed ranks and to a man denied the truth of the story. Edwards was smeared as a liar. It was not until twenty-four years later, after Cleveland and most of the witnesses were dead, that a doctor revealed the actual story and exonerated the reporter who had told the truth.

Did any of it matter? Probably not. The passage of the silver legislation did nothing to slow the depression. The country limped on for another four years before finally pulling out of the economic doldrums, in part as a result of the discovery of gold in Alaska.

History would judge Cleveland as one of our mediocre presidents, more honest than competent. But it has to be said of him that he was willing to take a substantial risk with his own health to keep the public in the dark and, as he thought, to calm the nation’s fears.

Please subscribe and share with others.

The Wall Street Journal says God Save Benedict Arnold “propels readers into the brutal action with vigorous prose and sentences that are often short and pugnacious—much like Arnold himself . . .” Click the image to get a copy delivered to your door:

Another good read and an interesting one that could have had much different consequences.

They made em tougher back then, ouch!