As the Great Depression descended on America in 1930, folks sang lyrics written by Dorothy Fields:

And if I never had a cent,

I'd be rich as Rockefeller,

Gold dust at my feet,

On the sunny side of the street.

Oil has been a reliable path to extraordinary wealth for the past century and a half. Not just Rockefeller but Getty, the Koch brothers, and many more of the world’s billionaires have sucked their riches from the teat of the petroleum well. Yet the one man most responsible for the industry in America was not among them.

Before petroleum, the dark world was lit only by candles and whale oil lamps. By the middle of the 1800s, whaling had become the fifth largest industry in the United States. The hunt had so decimated the population of leviathans that whalers had to venture ever farther into the Pacific Ocean to find targets for their harpoons.

Searching for an alternative, some suggested “rock oil,” a black, gooey substance that oozed from the ground in various places. Indigenous people in America had used it as a medicine. Early settlers thought of it as a balm for burns and a cure for indigestion. Experiments had shown that when distilled it yielded a burnable liquid dubbed kerosene. How to amass the oil in bulk remained a problem.

At this point, Edwin Drake entered the picture. Born in eastern New York in 1819 and raised in Vermont, he had worked odd jobs for a number of years before finding steadier employment as a train conductor. His railroad career was cut short by an illness that may have been multiple sclerosis.

During the 1850s, some businessmen had formed the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company (later called Seneca Oil). They knew that the oil seeped from the soil along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, about forty miles south of Erie. They hired Drake to investigate the commercial possibilities of petroleum in the area.

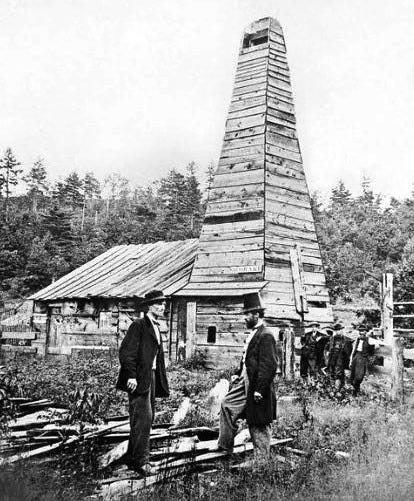

In the spring of 1858, Drake ventured to Titusville and introduced himself as “Colonel” Drake, a title he assumed to impress the locals. At first he hired men to dig a hole with the hopes that the oil would accumulate. It filled with water instead.

In May 1859, Drake decided to try another method. He hired a blacksmith named William “Uncle Billy” Smith, who had experience drilling salt wells. Uncle Billy sank a well near the creek. The task was frustrating — the hole kept collapsing and filling with gravel before he reached bedrock.

Drake came up with the idea of lining the drill hole with cast iron pipe, which Smith pounded down the opening using an oak battering ram. He inserted the drill through the pipe and continue deepening the hole.

The steam-powered drill made slow progress, about three feet a day. Locals laughed at “Drake’s Folly.” Executives at the Seneca Oil Company decided it wasn’t worth investing any more money in the venture. But Drake had become obsessed. He borrowed five hundred dollars and continued to drill with his own money.

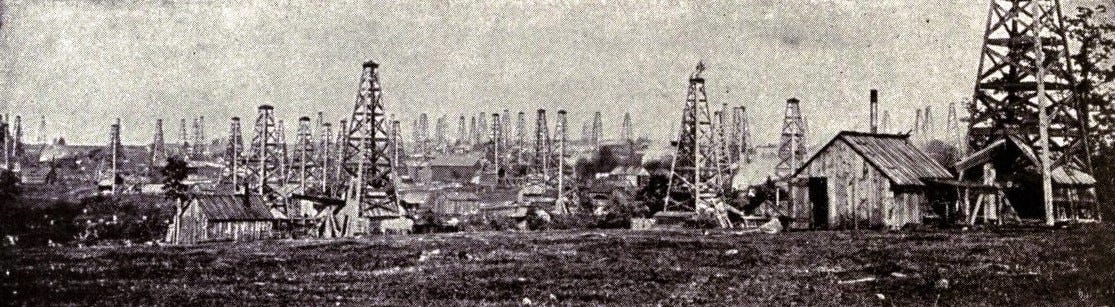

By Saturday, August 27, 1859, Drake’s well had reached a depth of 69 feet. When he returned on Monday, he found that Uncle Billy had spent the Sabbath pumping oil from the well and had already filled an array of barrels and tubs. Drake’s method was a success. Others saw the potential and rushed to the area. They drilled faster and deeper than Drake. Three years later, northwestern Pennsylvania was producing three million barrels of crude a year.

The Pennsylvania oil boom lasted until 1901, when more productive wells were sunk in Texas, California, Wyoming and other western areas.

Unfortunately for Drake, he had not thought to take out a patent on his idea, which continues to be the basic form of oil drilling to this day. In 1860, his employers fired him. Drake invested his savings in unsuccessful oil speculation — by the end of the Civil War, he was dead broke, his health deteriorating. In 1872, the state of Pennsylvania awarded him a meager pension. He died in 1880 at the age of sixty-one.

In 1896 a fly lit in the ointment. A Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius, calculated that according to the laws of physics an increase in carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere would result in significant warming. Although Arrhenius won the Nobel prize in 1905, few paid heed to what his work implied about the continued burning of fossil fuels. The motor car was becoming all the rage.

By the time the danger was recognized, the allure of wealth and the convenience of a fossil-fuel economy posed barriers to effective action. The greenhouse effect began to alter the climate sooner than predicted. Extreme storms, melting glaciers and the extinction of species accelerated. So too did the mantra “drill, baby, drill.”

In the past week, the United States has, once again, thrown in the towel on the fight against climate change. Oil has won out — for now. But last year’s hurricane in North Carolina and the recent fires around Los Angeles have alarmed many. The threat to today’s children has grown unacceptable — the promise of renewable energy shines ever brighter. More and more citizens are calling for action on a wide scale. Hope remains elusive, but it remains.

Morning Jack. I love you Talking to America and I learn so much history from you. Global Warming has been an issue for a while now and, yes, we can always hope things will change.

Oh, Jack, you have done it again. Such a great story, so little credit where credit is due, as well the allure of riches that always seems to win out.