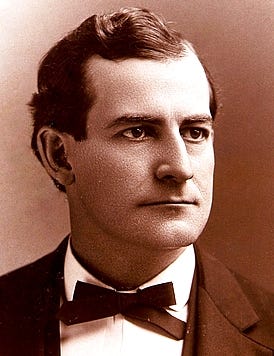

The tiny hamlet of Upper Red Hook, New York, a couple of miles from my house, is not likely to receive a visit from a major-party presidential candidate during the 2024 election season. But in 1896, William Jennings Bryan, the youngest man ever to run for the office, did drop by. Bryan planned to take break there from his hectic campaign and to catch some fish in nearby Spring Lake, but a salute by a local gun squad and a serenade by a brass band disturbed his quiet.

A Democratic congressman from Nebraska, Bryan was running an uphill race. His predecessor, Grover Cleveland, had overseen a major financial collapse in 1893. The depressed economy dominated politics. The thirty-six-year-old Bryan thought the solution was to expand the currency supply by minting silver. His opponent, William McKinley, backed by banking interests, stood firm for the gold standard.

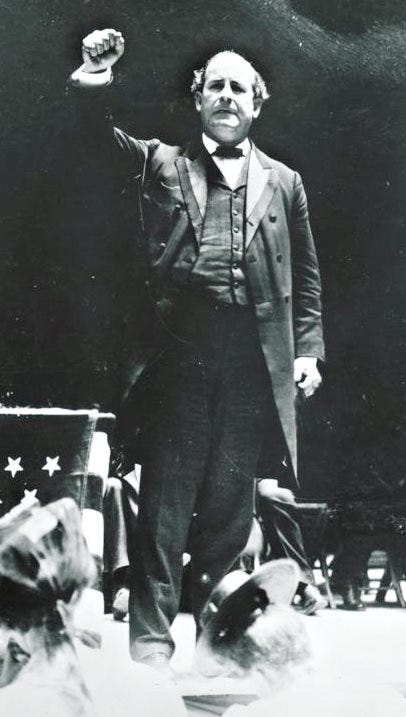

One thing to know about Bryan, he liked to talk. Having delivered public addresses since the age of four, he invented the stumping tour as a campaign tool. During the 1896 campaign he gave more than six hundred speeches, reaching an audience of five million voters. Nevertheless, McKinley won handily.

An advocate of independence for Cuba, Bryan raised and led a regiment to fight in the 1898 Spanish-American War. But he was also an anti-imperialist — he was appalled when the United States took possession of the Philippines.

He and McKinley staged a rematch in 1900, which Bryan said was a “contest between democracy and plutocracy.” A progressive champion of the farmer and working man, he had gained the nickname “The Great Commoner.” McKinley won again.

Nothing if not determined, Bryan took up the Democratic banner again in 1908, this time losing to William Howard Taft. He went on to advocate for an eight-hour day, the rights of unions, and women’s suffrage. He served as Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State when the Democrats finally regained the presidency.

Bryan’s life is an object lesson to those who like to look at the world, and at politicians in particular, in black and white. Sympathetic to ordinary people, Bryan worked tirelessly to make the world a better place. But he is today most noted for an incident during the hot summer of 1925, when he was sixty-five. It was known as the Monkey Trial.

Some will remember the 1960 film Inherit the Wind, a classic courtroom melodrama. Fredric March plays a thinly veiled Bryan. Spencer Tracy depicts the crusading lawyer Clarence Darrow. The issue is a Tennessee law that made the teaching of Darwin’s theory of evolution in public schools a crime.

Fundamentalist Christians were making a comeback at the time, with evolution as their main target. Bryan, converted at a revival meeting, was a zealous spokesman for old time religion. He taught Bible classes, plugged prohibition, and was one of the first to preach religion on the radio.

The movie offers an interesting glimpse of the culture wars of that era. Darrow, carrying the flag of science and modernity, came up with the ingenious ploy of calling Bryan himself as an expert witness on the Bible. He then proceeded to turn him into a buffoon, a throwback devoted to the benighted principles of the middle ages.

The Spencer Tracy character warns: “Fanaticism and ignorance is forever busy, and needs feeding.” It wasn’t until 1968 that the Supreme Court barred as unconstitutional the teaching of religious dogma in public schools. We’re still the only country on earth where evolution is “controversial” — two-thirds of evangelical Christians believe that humans have existed in their present form since the beginning of time. The recent revival of “Christian nationalism” reminds us that we have to remain on guard against bigots like Bryan.

[Click HERE to view a clip from the movie]

But even in his lamentable stand against science, the Great Commoner was not entirely in the wrong. One of his objections was to “social Darwinism.” This was a pseudoscience that attached itself to the theory and that was used to oppress the poor, promote racism, and justify the forced sterilization of “inferior” humans.

Inherit the Wind depicts the great orator dropping dead at the conclusion of the trial while he tries to deliver yet another speech to an audience who have lost interest in him. In real life, his reputation in tatters, he died in his sleep five days after the trial, on July 26, 1925.

God Save Benedict Arnold has been named a finalist for the 2024 New England Book Awards. Click the image to order a signed copy. Makes a good gift.

I love that each week your Talking to America about history is new for me. A very good article about Bryan. Thanks again.

Amazing , complex and thought provoking. It is as true today as then that there is a confusion between "the common man" and freedom.

Advocating for an eight-hour day, the rights of unions, and women’s suffrage was ahead of his time. Yet demanding Bible teaching is against everything our Constitution stands for and it is still a major argument.

Thank you Jack - as always you offer and share your knowledge with wit and great writing.