In the past week, a school bus crash in Florida killed eight passengers and injured forty-five others, some critically. It happened at 6:30 in the morning northwest of Orlando. The “retired” school bus, a news account said, was sideswiped by a pickup truck driven by a man under the influence. The bus broke through a fence and flipped over.

The victims were agricultural workers, Mexican nationals on their way to a watermelon farm to harvest crops. They were in Florida as part of a guest worker visa program for agricultural workers.

Transportation-related accidents account for nearly half of worker fatalities in the agriculture sector. Congress passed a law requiring seat belts in vehicles carrying these workers to their jobs. The Florida Fruit & Vegetable Association has called the new requirement “impractical.” It takes effect June 28.

Alfredo Tovar Sánchez, twenty years old, was one of those killed. He left behind a young daughter.

Americans often speak with pride and nostalgia about the “family farm.” But we have always taken a dim view of the migrants who do much of the work in our fields. During the Great Depression, the harvesters were known as “fruit tramps” or “Okies.” These migrants, most of them white Americans, were seen as dishonest intruders who sponged off the government.

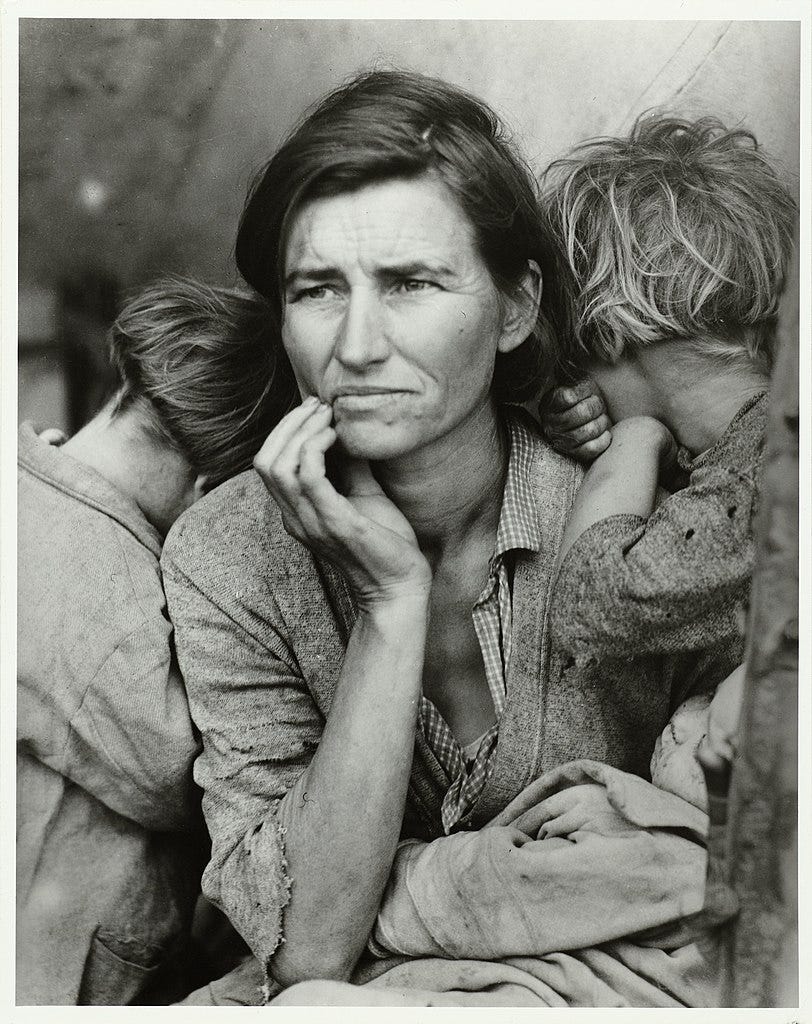

One story from that era reflects the complicated assumptions we often bring to the subject. It concerns a portrait taken by the renowned photographer Dorothea Lange in March 1936. Some have called it the most famous photo ever taken. The image, labeled “Migrant Mother,” became an icon of the era, a record of both the suffering and the strength of everyday Americans. It showed a woman, grim and worried, holding a baby. Two more children are leaning against her.

Lange had snapped the picture at a pea-pickers camp near San Luis Obispo, California. “I did not ask her name or her history,” Lange admitted. She recorded only the woman’s age — thirty-two. The migrant and her children, Lange said, were destitute. They had been forced to sell the tires of their car to buy food. The nameless woman “seemed to know that my picture might help her.”

Lange took the picture as part of a project for the Farm Security Administration. The goal was to show the conditions that the Depression had visited on farm workers and to support efforts to bring them some relief. It was part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. So popular was “Migrant Mother” that it was widely published in newspapers and magazines. It turned up in history books and on tee shirts and postage stamps.

The real story behind the photo did not become generally known until 1978, thirteen years after Lange’s death. The name of the “migrant mother” was Florence Owens Thompson. She said that she felt “exploited” by the portrait. Most of the details that Lange had given were incorrect.

Thompson, a widow with six children, had resorted to farm labor to support her family. She was not a pea picker. Usually she picked cotton, five hundred pounds of it a day.

The family had only been at the camp because their car had broken down on their way to a job picking lettuce. They had not sold their tires. Florence’s companion, the father of her infant daughter, was in town getting parts to repair the car. Yes, they were poor. “We just existed,” she said. “We survived, let’s put it that way.”

Although those who saw the photograph usually assumed Florence was white, she had in fact been born in Oklahoma to parents who were both Cherokee. How might viewers have reacted to her portrait if they had known the truth?

After World War II, she married George Thompson, a hospital administrator and settled down in Modesto, California. She died in 1983 at the age of eighty. Her daughter said that Thompson was “a very strong woman. She was a leader.”

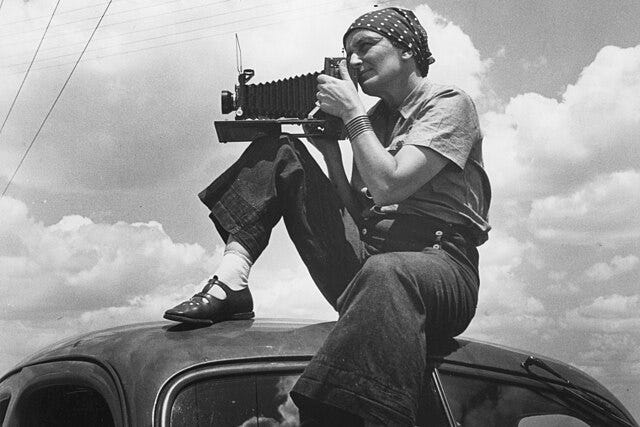

Dorothea Lange was also a strong woman. She overcame childhood polio and was dedicated to using her keen eye as a photographer for doing good. In addition to documenting the Depression, she made a record of the Japanese Americans who were interred during World War II. Her later photo essays also sought to uncover injustices so easily overlooked.

But even she, in a hurry to meet a deadline, failed to take the time to really see the woman whose face she would put before millions. She made an assumption and moved on. As we all do.

Jack, how do you do it? Another heartbreaking story that tells the facts behind a familiar photo, thank you.

"As we all do" - indeed.