The wars and politics that dominate our headlines are a large part of history—but not the only part. Play and sports and sheer fun have their place, too, in the crazy quilt of the past.

I’ve been reading a book entitled The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City. It’s a history of baseball combined with highlights of the epic story of America’s greatest metropolis.

By a happy coincidence, both the Yankees and (can it be?) the Mets are contending in this season’s playoffs. Kevin Baker, the author of this authoritative volume, marshals enough anecdotes, surprises, color, and humor for a stack of books and tells the multifaceted story of athletic skill, dirty tricks, and big money as if reporting on a high-speed car chase.

To begin with, he names names. Who doesn’t know the Mick and the Babe and Joltin’ Joe and Pee Wee and Mr. October and the Say Hey Kid? Fewer can probably identify Sal the Barber, the Curveless Wonder, Twinkletoes, Ducky-Wucky, or Death to Flying Things, except to know that these are certainly good ball-park monikers.

You might think the story would start with Abner Doubleday’s invention of the game at Cooperstown back when. But the author puts that myth through the shredder quickly. Abner, he assures us, may have fought at Gettysburg, read Sanskrit, and “served as president of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society. But he did not invent baseball.”

Nor was baseball first played on the remote shores of Otsego Lake. It was, as Baker establishes, an urban game from the beginning. When baseball began to be played in an organized way in the 1840s, there were many different sets of rules. The version that stuck was called the “New York game.”

New York and Brooklyn boasted fifty amateur baseball clubs in 1860. The sport, and New York along with it, grew at a frenetic pace after the Civil War. The rough city was the perfect place for a game marked by “gambling, brawling, and drunkenness, on and off the field.”

In early games a keg of beer was placed at third base to allow any player who made it that far to wet his whistle. “Umpires were regularly bombarded with pop bottles, eggs, beer bottles . . . Two were actually killed in the minor leagues.”

Baker recounts a brawl in Boston in 1894. Sliding into third, Tommy “Foghorn” Tucker of the Boston Beaneaters kicked John “Muggsy” McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles in the face to set off the donnybrook. The ensuing melee “swept up both teams and much of the crowd, culminating in a fire that consumed the old South End Grounds, along with 170 neighboring buildings.” Baker wryly adds, “Even the Yankees never burned down Fenway Park.”

As he sprints through the years, the author leaves a trail of fascinating information. “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” for example, was written in 1908 by Jack Norwith, who “had never been to a baseball game.” The tune, said to be the number three most played song in American history after “Happy Birthday” and the national anthem, celebrates the joy of fandom:

Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack,

I don't care if I never get back . . .

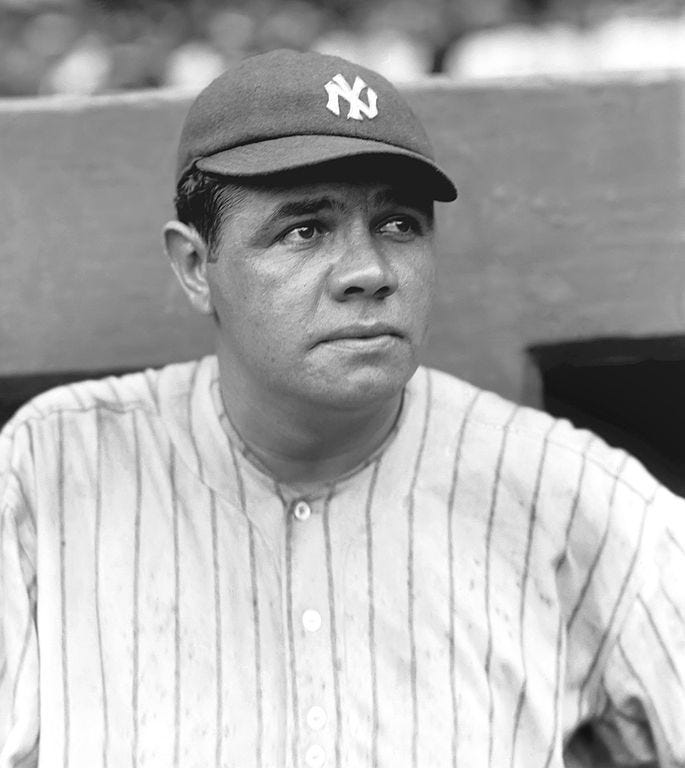

The book naturally celebrates Babe Ruth, not just as a larger-than-life personality but as one of the most talented athletes ever to play the sport. Rising from a broken home and deep poverty, Ruth was “the patron saint of American possibility.”

At twenty-one the Babe was the best left-handed pitcher in baseball. In two different seasons he hit “more home runs than any other team in the American League.” He hit 198 homers longer than 450 feet, far exceeding the efforts of later, steroid-juiced batsmen. A teammate put it succinctly: “All the lies about Ruth are true.”

Ruth teamed up with his unassuming but hard-hitting teammate Lou Gehrig to lead one of the greatest teams of all time, the 1927 Yankees. During that fabulous year at the peak of the Jazz Age, the two competed for the long-ball title. Gehrig led with 45 homers by September 6. Ruth came alive during the rest of the month to end up with a record 60 four-baggers.

The Yanks demolished the Pirates in the 1927 World Series. They swept the Series again the following year, this time against the Cardinals, with Gehrig hitting four homers in four games and Ruth scoring nine runs on ten hits.

If the Babe dominates the imagination of New Yorkers, Lou Gehrig lives in their hearts. The “Iron Horse,” was born in the city and spent his entire career with the Yanks. He played in 2,130 consecutive games, a record that would stand for 56 years. He took himself out of an early-season game in 1939 when it became clear he was suffering from an incurable neuromuscular illness. The player who called himself “the luckiest man on the face of the earth” died two years later at the age of thirty-seven.

Baker ends his book at the close of the World War II era. Perhaps this is only the seventh-inning stretch and he will pen a sequel that will awaken memories of the Yanks and Dodgers of the Fifties and the Mets of 1969 and 1986. Maybe it will even feature the subway series of 2024. Anyway, for fans, there’s always next year.

Click the image and pick up a signed copy of GOD SAVE BENEDICT ARNOLD:

Subway series may be looming. Mets have moved on and the Yanks are on the verge. Baseball is a NYC game.

Even though I'm not a baseball fan, I really enjoyed this story of Talking to America. Who doesn't know about the Babe and most of all the great Lou Gerig