Temple Grandin was a problem child. Born to a well-to-do Boston family in 1947, she stiffened in her mother’s arms as an infant. She was slow to develop language skills. She erupted into tantrums. At two, she was diagnosed as “brain damaged.” She could be extremely focused but was antisocial. Doctors recommended that she be institutionalized and her father agreed. Her mother instead sought out a speech therapist who helped Temple get past the extreme frustration of not being able to communicate.

It was the beginning of a long process by which Grandin was able to adapt to a world which seemed to have no place for her. A self-described “nerdy kid,” she was relentlessly taunted, bullied and ridiculed in school. Her mother finally found a school for “potentially gifted” children who could not flourish in an ordinary setting. “I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong,” Temple remembered. “I had an odd lack of awareness that I was different.”

With the aid of mentors and educators, she was able to earn advanced degrees in human psychology and animal science. She found that she had an affinity for animals, particularly cattle. She did not oppose the use of livestock for meat, but she felt that the animals should be afforded a decent life and painless death. They deserved respect. She became a designer of slaughterhouses.

In her adolescence, Grandin had experienced what she called “stage fright all the time for no reason.” She fabricated for herself a “squeeze machine,” based on the squeeze chute that held a cow for veterinary procedures as well as for slaughter. It was a device that would hug her body with gentle pressure. She found that it tamped down anxiety.

“I know what it’s like to feel fearful and scared,” she said. She could visualize what the animals heading toward their inevitable fate would see and hear and how they would react. Her insights led to animal handling facilities that leave cattle far less stressed. Her designs are now used widely in the meatpacking industry.

Grandin referred to herself as an “anthropologist on Mars” — always trying to learn the customs of an alien environment. She did not automatically “get” many aspects of social interaction. Only by observing how others acted and mimicking their behavior could she fit in.

It wasn’t until later in life that Grandin was diagnosed with autism. The syndrome, as it’s understood today, had been given a name by psychologists in the 1940s. It was not a specific disease but a spectrum of traits and behaviors. Those afflicted range from the severely disabled to high-functioning individuals like Grandin. Problems with language, with sensory overload, and with the recognition of social cues are the most common symptoms.

The labeling of mental conditions has a long history. For centuries, the diagnosis of hysteria was applied to people, especially women, with a variety of symptoms. Later, the term neurotic supposedly described a distinct class of individuals. Today, both concepts are obsolete. Homosexuality was once labeled a mental illness. So was the desire of enslaved Africans to run away from their “owners” — it was called “drapetomania.”

The understanding of autism has evolved. It is now related to the idea of neurodiversity, the concept that everyone’s brain develops individually. It’s the recognition that the labels assigned to people are artificial and often reflect society’s biases. In reality, different skills and capabilities and limitations combine to create a unique person. There is no clear divide between normal and abnormal. A person who is neurodivergent might be seen as handicapped — or as a genius in a particular area.

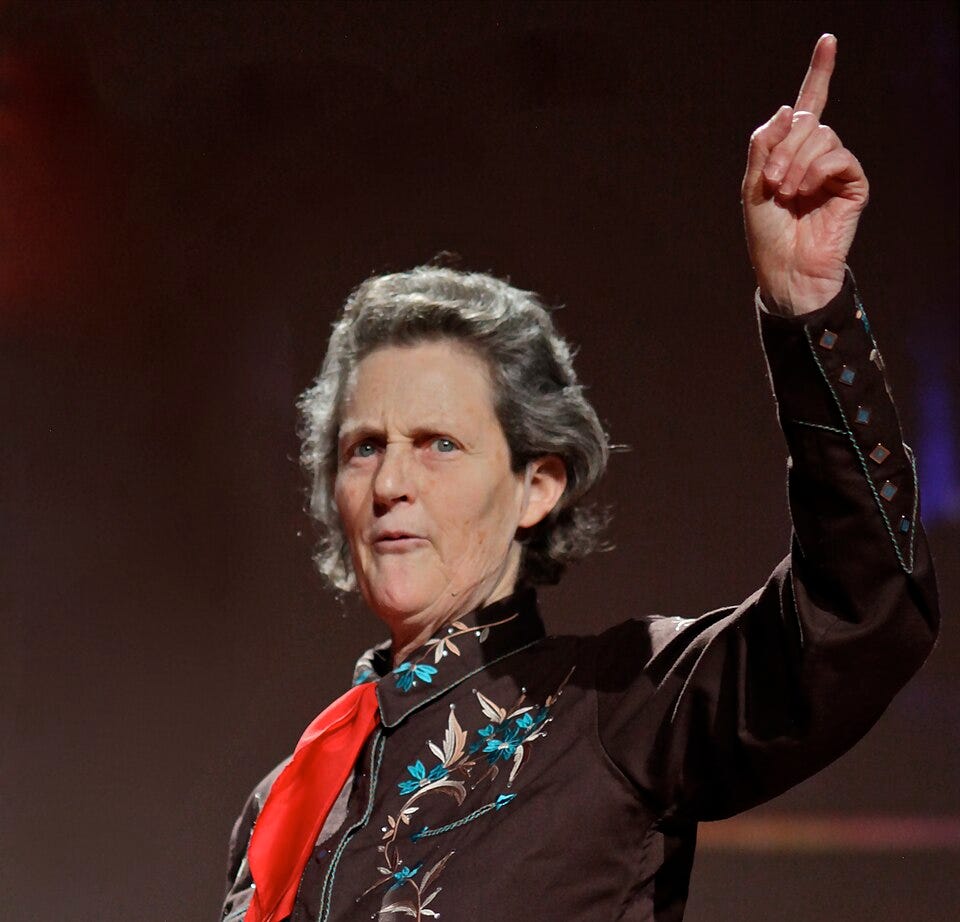

Temple Grandin used her native skills for extraordinary achievements. She has published numerous books, including Thinking in Pictures, and many scientific papers. She has been a tireless advocate for the welfare of autistic people, as well as for the humane treatment of animals.

Lately, controversy has flared over autism, in part because of the insistence by the U.S. Secretary of Health & Human Services Robert Kennedy that the country is experiencing an”epidemic” of autism. The cause, he asserts, involves childhood vaccinations and other “toxins.” Scientists have studied and discarded this hypothesis. The roots of autism, they say, are complex and largely genetic. The rising incidence of the syndrome is a result of increased awareness and changes in the criteria for diagnosis. Kennedy’s dehumanizing description of those with autism was seen by advocacy groups as further stigmatization.

The neurodiversity movement has tried to get across the idea that, contrary to government decrees, diversity is built in to human nature. Brains develop and work in different pattens. Temple Grandin thinks in pictures, not words — this gives her unique abilities. Some who are touched by traits like dyslexia or attention deficit disorder might need accommodations and support to fulfill their potential.

The message that Temple Grandin has tried to get across is that those in our society with special needs simply deserve respect. They are struggling not because there’s something “wrong” with them, but because of how we define what’s normal. Those who don’t fit in are too often deliberately excluded, belittled, and scorned.

“I think lots of times there are things that are missing from my life,” Grandin told the psychologist Oliver Sacks. But, she said, “if I could snap my fingers and be nonautistic, I would not — because then I wouldn’t be me.”

I had never heard of Temple Grandin and very thankful to you Jack for this really, really, good Talking to America. It's wonderful to be "special" and damn straight, should always be treated with respect and kindness. I love that Temple was happy being her. Wow

Oh, Jack, so nice to think about Temple Grandin again, I read one or two of her books long ago. And a brilliant way to segue into the RFK craziness that we now are dealing with.