The Founders’ relation to slavery is a touchy topic. Lately, a number of states have passed laws restricting teaching about the subject in schools. In Iowa today, it’s not clear even whether a teacher can label slavery as “wrong.”

More on this in a moment.

I’ve always found a passage in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to be particularly poignant and insightful. Claudius has recently killed his brother, married the queen, and become the ruler of Denmark. Now, he’s having qualms about his deeds. “My offence is rank,” he says to himself, “it smells to heaven.”

His guilt weighs on him. He kneels to ask God’s forgiveness. But, he admits, “pray, can I not.” And he well understands why:

. . . since I am still possessed

Of those effects for which I did the murder,

My crown, mine own ambition, and my queen.

May one be pardoned and retain th’ offence?

Claudius faces a familiar and all too human dilemma. He wants to ease the burden of guilt, and he wants to indulge in the fruits of his crime. All of us, at one time or another, have failed to live up to our ideals and have been reluctant to relinquish the enjoyment that results from that failure.

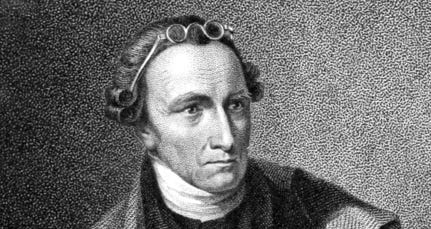

Claudius’s problem is reflected in the life of Patrick Henry. In 1775, on the eve of the Revolutionary War, the Virginia firebrand famously proclaimed:

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Henry acted out his speech by holding up his wrists, pressed together as if in shackles. At the time, he himself held dozens of human beings in slavery.

And so it was with many of the Founders. Twelve of our first eighteen presidents were enslavers. Their offenses smelled to heaven. Slavery very much depended on chains, the whip, and most of all the degradation of men, women, and children to a status their “owners” deemed less than human.

So, two years before his quotable peon to liberty, Patrick Henry writes a letter to Robert Pleasants, an early Virginia advocate for the abolition of slavery. He agrees with Pleasants that slavery is an “abominable practice . . . a species of violence and tyranny.” He goes further—slavery is “as repugnant to humanity, as it is inconsistent with the Bible and destructive to liberty.”

But—here the ghost of Claudius materializes to haunt him—he is compelled to retain his slaves, he writes, “by the general inconvenience of living without them.” He is willing to suffer death rather than give up his own freedom, but the advantages of enslaving his fellow humans, the “convenience” of wringing his bread from the sweat of other men's faces, that’s something he just cannot let go of.

Henry is troubled by his own behavior, but, like Claudius, cannot escape it. The sole duty he can pay to virtue, he says, is to recognize “the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and to lament my want of conformity to them.”

He extends his tortuous logic even further. “Let us transmit to our descendants,” he writes, not just our slaves but also “pity for their unhappy lot and an abhorrence for slavery.”

What? This is the twisted view of a man who, again like Claudius, wants what in common parlance is known as having your cake and eating it too. Unlike George Washington, who at least freed the people he had enslaved on his death—Patrick Henry passed on perpetual “ownership” of sixty-nine humans to his heirs.

It’s easy to dismiss Henry’s letter as sanctimonious bullshit. Many of the Founders issued similar protestations of regret. Madison called slavery “the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.” He kept more than a hundred people in chains. Jefferson wrote that because of the institution of slavery, “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just.” He forced scores of humans to toil on his plantation and routinely raped enslaved women.

But Shakespeare’s portrayal of Claudius’s dilemma is not meant to ennoble a character who is, after all, a murderer and a coward. It’s rather to hold the mirror up to the audience, so that we might better recognize our own occasional preference for “convenience,” and, perhaps, rectify it.

Henry ends his letter on a tragic note. Contemplating slavery in America, he writes, “gives a gloomy perspective to future times.” The labor and the very lives of millions of enslaved people stolen from them. The death of more than six hundred thousand soldiers in the fight to end the “abominable practice.” The crippling stigma of racial stereotyping that was enforced by law for a hundred years after the Civil War and that continues to shame the nation even today. Yes, a gloomy perspective.

Claudius ends his speech with the cry: “Help, angels!”

Another powerful piece, Jack. And very relevant in today’s environment.

A powerful piece. And we continue to dance with the devil in many ways. Consider the continuing reliance on fossil fuels. The expression "pay forward" comes to mind. What is it that we leave for our heirs?