Just sixteen in 1889, Victor Heiser was tall, blond, pink-cheeked, and studious. His father, George, had fought in the Civil War and now operated a modest general store in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The family lived upstairs.

Victor’s mother, Mathilde, born in Germany, hired tutors for her son, determined that he would not end up laboring in a steel mill. Johnstown was a center of industry nestled in the mountains east of Pittsburgh. The small city occupied a tight valley where two smaller rivers joined to form the Conemaugh River.

On May 31, 1889, rain came down an inch an hour. By early afternoon, the water was two feet deep in front of the Heiser store. George sent Victor out to the new barn behind the store to untie the horses. He was afraid the animals might be strangled if the river continued to rise.

What he didn’t know — what no one in town knew — was that around noon, water had begun to lap over the South Fork Dam fifteen miles up the valley. The seventy-foot-high earthen dam held back a lake two miles long that contained twenty million tons of water. It was a fishing resort for wealthy families from Pittsburgh, people with names like Carnegie and Frick.

The dam had not been well maintained. When water breached its top, it began to erode the dirt on the downward slope. Just before four in the afternoon, a witness remembered, “The whole dam seemed to push out all at once.”

The force of the water shoved this massive wall of dirt, cement and stone riprap down the valley that zigzagged between hills to Johnstown. As it went, it snapped huge trees, and scooped vines and bushes, fences and mud and houses, into a wall of debris. It paused momentarily at a railroad bridge, built up new momentum, then broke through and went rushing ahead at high speed.

The flood was not a wave of water. Fronted by a black mist of spray and dirt, it was a solid wall of debris. “It just seemed like a mountain coming,” a witness reported. On its journey, it swept over a wire factory and picked up miles of coiled barbed wire that mixed with the other wreckage, including steam locomotives.

Victor Heiser heard the “dreadful roar” of the approaching mass. He froze for a moment. His father, upstairs in their home, frantically motioned for him to climb to the roof of the barn. Victor went up the stairs and out a trap door. He watched his home being “crushed like an eggshell,” just before the flood shoved the barn off its foundation.

The building began to tumble. Victor jumped and dodged, trying to stay on top. He sped toward a neighbor’s house. At the last minute, he leapt to that roof. Another house crashed into this one. He clung to an eave, sure that letting go meant death in the grinding mass below. He lost his grip and fell with a thud, landing back onto the roof of his family’s barn.

Now he was spinning down the great gush of muddy flood water. He saw a fruit dealer whose shop was just up the street. The man went speeding by with his whole family, clinging to a barn floor before a melee of wreckage heaved up and crushed them all.

Victor’s barn struck the heap of trees and beams, buildings and rail cars piled up at the stone railroad bridge just below the city. Clinging to his raft, he slipped away into slower water. Finally, he managed to leap onto the roof of a brick building, where he took refuge with a dozen others.

Debris continued to mount at the stone bridge. As night fell, this heap caught fire, ignited by stoves in the many houses piled there. Although bystanders managed to save some, dozens of men, women and children remained trapped inside their own displaced homes. They burned to death, their screams haunting the darkness.

In the morning, the scope of the disaster began to take shape. Those who had survived the onslaught, or had avoided it by running for high ground, were wet, cold, and hungry. Many were injured, some naked. Floating corpses, animal and human, made the water undrinkable.

But soon farmers showed up, bringing wagonloads of food and dry clothing from the country. “People who had hardly known each other before the flood embraced one another,” one survivor remembered. “All ordinary rules of decorum and differences of religion, politics and position were forgotten.”

The grim search for loved ones began. Victor Heiser remembered, “Day after day, I searched among the ruins and viewed with a tense anxiety the hundreds of corpses constantly being carried to the morgues.” He found his mother’s body — his father was one of many lost without a trace. At least 2,200 people had been killed.

Relief efforts were organized. The country, indeed the world, responded to the worst civilian disaster to that time in American history. Nearly $4 million was raised. Clara Barton, who had founded the American Red Cross a few years earlier, arrived with fifty doctors and nurses.

Johnstown was largely a manmade disaster. Some residents sued the rich folks who had been careless in keeping up their fishing lake. The lawsuits failed and no compensation was ever paid.

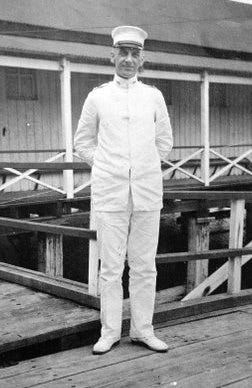

Victor Heiser, an orphan at sixteen, later worked his way through medical school. As public-health officer and physician he fought diseases around the world. Because of his efforts to bring sanitation and vaccines to poor countries, he was credited with saving two million lives.

Wow. An amazing story. One of the survivors lives to save millions. How precious one soul can be. Beautifully written, Jack.

A great history story Jack. Victor Heiser sure was a lucky and smart young boy and as an adult made his work to help so many others. I love the stories you bring to Talking to American