“Nobody made a greater mistake,” the statesman Edmund Burke said, “than he who did nothing because he could do only a little.” The rush of events these days makes many of us feel overwhelmed. Yet every event is shaped by the actions of people. One person can make a difference, often by inspiring others or becoming a catalyst for solidarity.

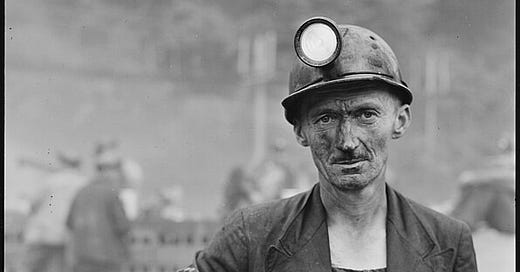

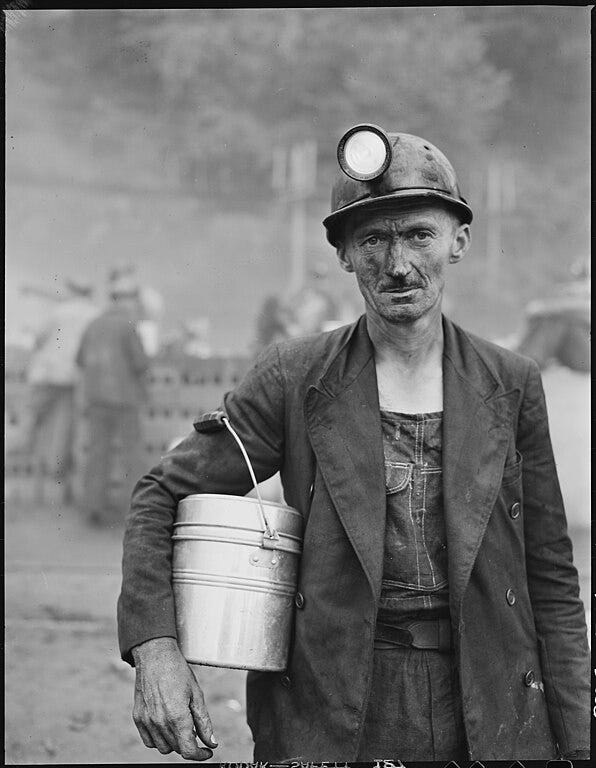

Born in 1912, Elizabeth Hayes grew up in a hard-scrabble mining town in the hills northeast of Pittsburgh, coal country. The town of Force, Pennsylvania, had been built by the Shawmut Mining Company to house its employees. Her father, Dr. Leo Hayes, was the only physician for twenty-five miles. He worked for the company; the family lived in a company-owned house. He sent six of his children to medical school. The youngest was Elizabeth, who became a doctor in 1936, a time when few women entered the profession.

After spending some years in private practice, Elizabeth volunteered as a tuberculosis researcher during World War II. Her father died unexpectedly a short time later. She rushed home and, because of the severe wartime shortage of doctors, took over his practice in Force.

The miners welcomed Doctor Betty, as she was called. Many had known her since she was a child. But looking around her hometown with the eyes of a doctor, Hayes saw problems everywhere. Most homes had no plumbing. Drinking water came from a common hand-pumped well. Privies were far too close to wells. During rainstorms, sewage ran into the unpaved roads where children played. People were getting sick; a serious typhoid epidemic was a danger

Hayes had the water tested in a laboratory, which verified the contamination. She told Shawmut managers the situation had to be remedied immediately. She accompanied miners to meetings with the company to demand action.

“I see no point in having well baby clinics when you feed these babies ‘toilet’ water,” she said. She threatened to quit if nothing was done. In the spring of 1945, the company accepted her resignation. More than 350 miners went out on strike to support her, closing two of the company’s most productive mines. Hayes continued to see patients.

The controversy hit the newspapers and wire services and Dr. Betty became famous overnight — some called her the miners’ Joan of Arc. A reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette began looking into the mining firm’s parent company, the Pittsburgh, Shawmut & Northern Railroad. That company had entered bankruptcy forty years earlier, but continued to be run by a court-appointed receiver who drew a handsome salary while the business lost money.

The issue reached as high as Harry Truman’s White House. His attorney general scheduled hearings. The ham-handed company sent movers to evict Dr. Betty from the house where she had grown up. She pressed charges. The action igniting a new wave of publicity. Although Hayes hated the notoriety, her biographer, Marcia Biederman, observed that being ”a smartly dressed, wisecracking career woman,” made her story eminently newsworthy and helped her cause.

The court put the company in the hands of a new receiver. He appointed a slate of company executives who agreed to all the workers’ demands. The miners went back to work in December 1945 after an eight-month walkout. Dr. Betty was rehired. The streets in Force were soon paved for the first time.

By 1947, when Hayes moved away to get married, sanitation problems had been remedied and many of the residents had received deeds to the homes they had long paid rent on. Elizabeth Hayes worked as a physician during the years afterward. She died in 1984 at the age of seventy-two.

In 2023, the state of Pennsylvania recognized Hayes’s courage and effectiveness by designating a portion of Route 255 as The Dr. Betty Hayes Memorial Highway. A state representative noted that she “devoted years of her life to fight against the inhumane conditions of the mining town she called home.”

At the height of her fame, folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote a song about Dr. Betty:

She went to the big shots of the Shawmut Company

She did not beg and she did not plead

She stood flatfooted and pounded the table

Sewer pipes and bathrooms are what we need . . .

Harlan County USA is Barbara Koppel’s moving 1976 film about a Kentucky coal miners’ strike over some of these same issues. To watch it on the Inernet Archive, CLICK HERE.

Seems like the "Do-Gooders" are always out numbered by the "Do-Badders", unfortunately!

Another wonderful story Jack and a pleasure to learn about this smart, caring and step up Doctor.