In 1931, Albert Speer, a German professor of architecture, listened to an orator in the back room of a dirty Berlin beer hall. The speaker began his talk “in a low voice, hesitantly and somewhat shyly.” He told of his anxieties about the nation. As he went on, he “spoke urgently,” Speer remembered, “and with a hypnotic persuasiveness.” His name was Adolph Hitler.

“The following day,” Speer wrote in his memoir, “I applied for membership in the National Socialist [Nazi] Party . . . I had no idea that fourteen years later I would have to answer for a host of crimes.”

Speer used his talent to design the rally grounds in Nuremberg where the Nazi Party held a series of massive rallies. Known as “Hitler’s architect,” the young professor was later elevated to Minister of Armaments and War Production. He oversaw the eviction of Jewish citizens from Berlin. As one of Hitler’s key operatives, he supervised the exploitation of slave labor. He enforced discipline with frequent executions. Many thousands of prisoners were simply worked to death.

Most German citizens of the time joined Speer in supporting the Nazi cause. They wanted to see Germany, defeated in the World War, return to glory.

Tens of thousands of young people joined Hitler Youth organizations. One who signed up in 1933 was Hans Scholl, the fifteen-year-old son of a liberal politician. His sister Sophie, three years younger, joined the girls’ section of the group in 1934. But both soon grew disillusioned with Nazi ideology.

The teenagers became active in an anti-Hitler youth group. They were questioned by the Gestapo in 1939 but soon released. Sophie became a kindergarten teacher, then enrolled in the University of Munich to study biology and philosophy. Hans was already studying medicine there.

In 1940, at the age of 19, Sophie wrote to her fiancé: “Although I don't know much about politics, I do have some idea of right and wrong. All that matters is whether we manage to hold our own among the majority.”

In 1942, their father, Robert, a critic of the Nazi party from the beginning, was imprisoned for making a disparaging remark about Hitler to a colleague at work. With the war raging, the question of how to respond to a dictatorship became increasingly pressing for liberal students.

They decided to form a group that they called the White Rose. They began to produce leaflets, arguing philosophically against Naziism. They quoted from the great German poets Novalis and Schiller.

At first, they mailed the literature to professors and students. Later they began to distribute notices more widely. They inserted leaflets into phone books in public booths. All were signed “White Rose.”

“Why do you tolerate these rulers gradually robbing you, in public and in private, of one right after another,” one leaflet asked, “until one day nothing, absolutely nothing, remains but the machinery of the state, under the command of criminals and drunkards?” They recommended sabotaging arms production and disrupting public ceremonies.

By 1943, they felt they were having an effect. The war was going badly for Germany and more citizens were questioning the regime. White Rose members became bolder, handing out leaflets in person and painting DOWN WITH HITLER on walls in Berlin.

That year, Hans and Sophie went to a Munich university carrying a suitcase full of leaflets. Sophie left stacks of them near the doors of classrooms. She tossed the rest over the railing of an atrium. A maintenance man, a Nazi party member, spotted her in the act.

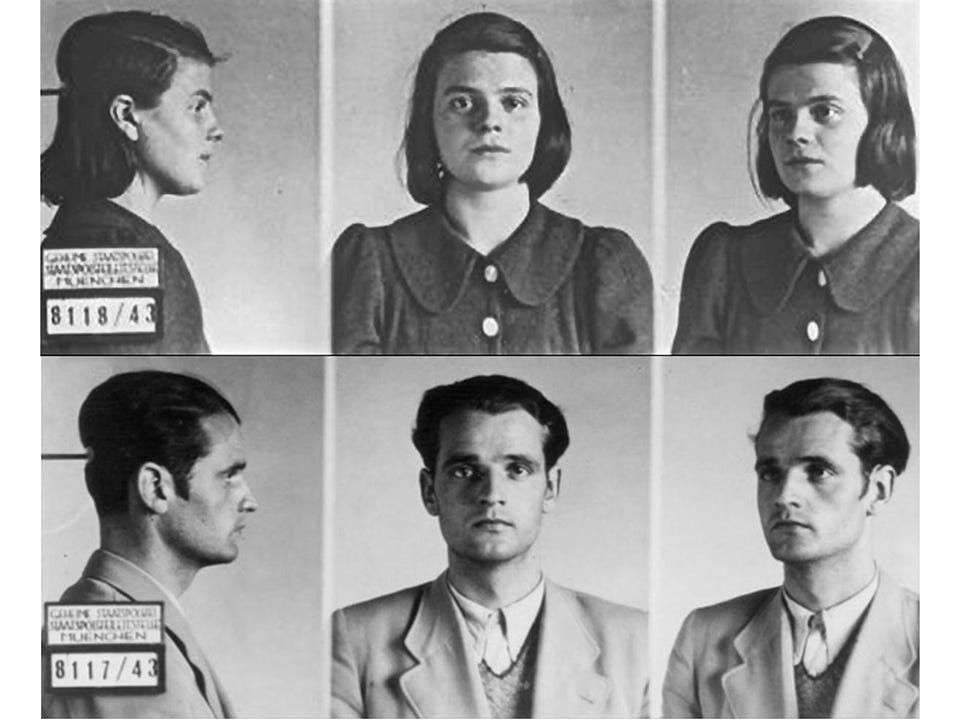

Both Sophie and Hans, along with another member of the group, were arrested by the Gestapo. At their trial, Sophie said, “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don't dare express themselves as we did.” They were found guilty of treason the same day.

Asked if she regretted her crime, Sophie answered, “I am, now as before, of the opinion that I did the best that I could do for my nation. I therefore do not regret my conduct and will bear the consequences that result from my conduct.”

A few months later, Royal Air Force planes dropped hundreds of thousands of copies of the students’ final leaflet from planes over Germany, raining their ideas onto those who had done nothing to stop the Nazi barbarity.

The document read, in part: “The day of reckoning has come. No threat can terrorize us. This is the struggle of each and every one of us for our future, our freedom, and our honor.”

After the defeat of Germany, Albert Speer, was tried for war crimes. He falsely depicted himself as a “good Nazi,” who knew nothing of the death camps and atrocities. He was sentenced to twenty years in prison. Released in 1966, he wrote two successful memoirs and lived a comfortable life until 1981, when he died of a stroke at age 76.

The day of their conviction in February 1943, Sophie and Hans Scholl were both beheaded by guillotine. Hans was 24 years old. Sophie was 21.

Great article Jack, Hans and Sophie are true heroes. If you want to see what we're up against today, just listen to PBS Commentator Amna Nawaz interview the Conservative pod-caster Michael Knowles during their Series "On Democracy". This guy will make your skin crawl. Scary!

The parallels are astounding. Thank you, Jack-as always