Thanks for subscribing and sharing.

This year marks the 120th anniversary of humans’ first powered flight. Bicycle mechanics Orville and Wilbur Wright are rightly famous for Wilbur’s 12-second, 120-foot hop over the dunes at Kitty Hawk in 1903. The first man to fly across the entire United States is less well known, but his achievement, in 1911, was as remarkable as it was demanding.

Calbraith Perry Rodgers was born in 1879, a few months after his father was killed by lightning. Cal enjoyed a privileged upbringing in Pittsburgh, but at the age of six he contracted scarlet fever—the illness left him almost entirely deaf.

As a young man, Cal developed a football player’s build and enjoyed yachting. In the summer of 1911, he paid the Wright brothers the equivalent of $25,000 in today’s currency to teach him to fly. The cost of the lessons was credited against the purchase price of a Wright airplane.

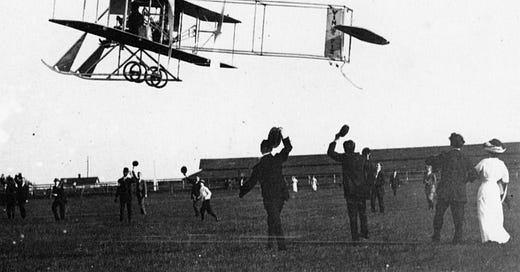

Rodgers’ biplane was an ungainly cross between a bicycle and a box kite: wide fabric-covered wings, a rudder and elevator flaps extending behind, and an engine that drove two rear-facing propellers by means of a chain and sprocket arrangement, all of it held together by piano wire. Two seats, no fuselage, no windscreen, no instruments. The pilot controlled the craft by pulling a lever that warped the wings and shifted the rudder. The plane took off and landed on wooden skids. The contraption was unwieldy and very sensitive to wind currents.

By August, Cal had gained his pilot’s license, the forty-ninth man in history to do so. The novelty of flying was exhilarating. “There’s nothing like it,” an early aviator said. “You’re there, watching the land glide by, bobbing and dipping as in a boat.”

While Rodgers was making money in Chicago giving rich socialites their initial flights, he heard that newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst was offering a prize of $50,000 to the first man to fly across the country in either direction. Contestants could pick their route as long as Chicago was one of the stops. They had to complete the entire trip in less than thirty days.

The tempting prize—$1.5 million today—was offset by the drawbacks. The Wright brothers declined to participate, figuring it would cost them at least $25,000 to mount an effort with no guarantee of success. There were no airports along the way; early planes could easily be damaged by landing in rough fields. The danger to the pilot was considerable.

Cal Rodgers was drawn to the challenge. J. Ogden Armour, the proprietor of a meat-packing empire in Chicago, offered to sponsor him. The company would pick up expenses and pay him five dollars per mile flown. He would advertise a new product from Armour’s soft-drink division, a grape soda named “Vin Fiz.”

Cal agreed. Two other fliers joined the attempt in September 1911, but both soon dropped out. Rodgers’ Wright-manufactured plane, named the Vin Fiz, was powered by a 35-horsepower engine that drove it along at fifty-five miles an hour. He hired one of the Wrights’ best mechanics to travel in a special train to help with maintenance and repairs. The train carried a sleeping car and a fully equipped workshop as well as an automobile for traveling to and from landing sites. Cal’s wife and mother went along to encourage him.

The aviator soared skyward on September 17, 1911, from Sheepshead Bay race course in Brooklyn. Flying over Coney Island, a cigar clamped between his teeth, he flung out advertising cards for Vin Fiz to the astounded crowds below—the product name was also painted on the underside of the wing.

Cal followed the Erie rail line through southern New York State. That first day, he landed at a fairground in Middletown, New York, having covered 84 miles in less than two hours. When he took off the next morning, the Vin Fiz rose too slowly, clipped some trees and wires, and crashed into a chicken coop. The accident left Cal with a sprained ankle. The mechanic and his helpers worked around the clock to rebuild the plane.

Back on course, Rodgers hopped from city to town along the route to Chicago. Obstacles or wind gusts resulted in several more crashes. Everywhere, citizens gazed skyward to take in the first flying machine they had ever seen.

From Chicago, Rodgers flew south to Dallas. By the time he arrived in San Antonio on October 23, delays had already put him beyond the thirty-day limit for the Hearst prize. Since he still had the backing of the Armour company, Cal was determined to continue. He headed westward to El Paso and followed the southern U.S. border. He had to cope with a cracked engine block, broken skids, and delays while awaiting calmer winds.

On November 5, he reached Pasadena, California, only twenty-three miles from Long Beach, where he intended to land on the shore of the Pacific. Flying on this final leg, the Vin Fiz suddenly lurched downward, fell 150 feet and crashed into a farm field. Cal, who had an uncanny ability to survive mishaps, suffered a concussion, burns on his face, and another badly sprained ankle.

After recuperating in a hospital for a few weeks, he took off once more on December 10. He had covered more than four thousand miles over eighty-two hours of total flying time. Finally, he descended onto the sandy ocean beach among a cheering crowd. In addition to his notoriety, Rodgers received $23,000 from Armour for his trouble.

The unprecedented advertising effort did not establish Vin Fiz among brands like Coca Cola. The fact that one critic referred to the taste as “a cross between river water and horse slop” may suggest why.

Cal Rodgers was on his way to becoming one of the best-known figures in aviation history—he was already making plans to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Three months after the cross-country ordeal, he returned to Long Beach to give a flying exhibition. He went up on April 3, 1912, zoomed over the roller coaster, lost control of his plane and plummeted into the surf. Cal Rodgers’ luck had run out—he was killed at the age of thirty-three.

(Thanks to Eric Snowden for aeronautical insight.)

Terrific tale and extremely well told. And unbeknownst to me previously. And Cal looked an awful lot like Paul Newman, yes?

Aviators are a rare breed. Chicken wire an canvas, geez!