“Speak softly and carry a big stick.” President Teddy Roosevelt’s motto from 1900 has long been considered good advice. Perhaps its time has passed.

This past week, the U.S. secretary of state, on a visit to Panama, brandished the formidable club of American military might but ignored the soft speaking part. He demanded “immediate changes” to that country’s policies. His remarks echoed those of the current U.S. president, who said of the canal, “We’re going to take it back, or something very powerful is going to happen.”

The brouhaha evokes one of the stranger adventurers in our country’s history. William Walker was a brilliant and accomplished young man from Tennessee. Born in 1824, he graduated from college at fourteen and picked up a medical degree five years later. He studied law in New Orleans and then moved to San Francisco to become a newspaper editor just as the 1849 gold rush was exploding.

Walker had come of age during a time of “manifest destiny,” a term coined in 1845 following the annexation of Texas by the United States. The Mexican War, which added the entire Southwest and California to U.S. territory, followed soon after.

An idealist of sorts, Walker saw a benefit in turning part of Mexico into a U.S. colony. He joined the popular practice of “filibustering.” Before it referred to an obstructive gabfest in the U.S. Senate, a filibuster meant a military expedition mounted by an ad hoc battalion of U.S. civilians into a foreign country.

In 1853, Walker and forty-five followers descended on Baja California, the long peninsula that stretches down Mexico’s west coast. He succeeded in capturing the regional capital and establishing a new “republic.” Volunteers streamed south from the U.S. to join his army.

Walker was an improbable conqueror. Barely more than five feet tall and slight of build, he lacked military training. Yet one of his followers said, “He exercised a magnetic attraction such as is rarely witnessed.”

It wasn’t enough. Discipline in his army faltered, many of his men deserted, and the venture collapsed. Yet when he returned to the U.S., Walker was proclaimed a hero. A jury refused to convict him of violating American neutrality laws. Soon he was organizing another army to go filibustering against a new target.

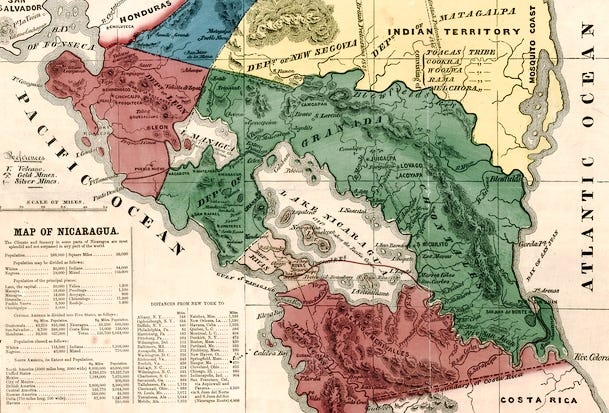

Before a canal was built across Central America, travelers to California could take passage to Nicaragua, ride a steamboat up the San Juan River, cross Lake Nicaragua, and need only a short stagecoach ride to reach the Pacific Ocean. There they could hop a ship north, dreaming of gold. This route was monopolized by a company owned by the wealthy U.S. shipping tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt.

In June 1855, Walker led a force of fifty-eight volunteers to Nicaragua. It was, he said, “a column of Progress and Democracy.” Walker joined with local soldiers on one side of a civil war. They won. Walker told his men, “We have come here as the advance guard of American civilization.” He made English an official language, rewarded supporters with confiscated property, and encouraged settlers from the U.S. to join him.

The U.S. government opposed his flouting of neutrality rules but in the end decided to recognize his new government. Walker organized elections of dubious honesty and soon found himself the president of Nicaragua. American newspapers gushed over his success. He was called the “hope of freedom.” Plays were mounted in the U.S. dramatizing his exploits.

At the time, the issue of slavery was increasingly dividing Americans. Southerners had a vision of adding Nicaragua to the Union as a slave state. Maybe Cuba, too. Walker, who did not own slaves himself, legalized the practice in Nicaragua and tried to drum up further support from slave interests.

In spite of his success, the adventurer made two political blunders. First, he revoked Vanderbilt’s charter and confiscated his steamboats, thereby making a powerful enemy. Next, he suggested that he might extend his filibustering to other Central American countries. Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador joined forces. With Vanderbilt cheering them on, they sent a 17,000-man army against Walker’s 2,500 men. By March 1857, Walker had been defeated, put aboard a U.S. Navy ship and sent home.

Again, he was lionized. President Buchanan invited him to the White House. He lectured widely and in 1860 published a book about his adventures. But the lure of filibustering soon drew him back to Central America. He teamed up with some local rebels in Honduras for another attempt to establish a colony. This time, his actions threatened British interests in the area. Pursued into the jungle, he was captured by men from the Royal Navy. They turned him over to local authorities. On September 12, 1860, the Hondurans put the Walker in front of a firing squad and shot him dead. He was thirty-six.

“He was no vulgar adventurer,” the New York Times wrote in its obituary. The article emphasized “his moral force and personal integrity.” The following April, the United States plunged into its own civil war.

That was hardly the end of U.S. involvement in the region. U.S. Marines invaded Nicaragua in 1912. The occupation, which lasted two decades, was intended in part to prevent any other nation from building a canal through the country to compete with the Panama Canal. That waterway, then being built under U.S. auspices, was completed in 1914. It was ceded to Panama in a 1977 treaty. Panamanians have so far not proven themselves entirely pliable to U.S. bluster

.

Morning Jack. Another really good Talking to America history lesson that I knew nothing about. Thank you

As Phyllis says, this is stuff I never learned in school. The discrepancy between what Walker was actually doing and how it was portrayed in Washington sounds familiar. Thanks for the lesson, Jack.