In the 1850s, a young woman named Eunice Newton Foote was the first scientist to identify what we today call greenhouse gases. She was also the first to recognize their potential effect on the earth’s climate. We have only recently come to understand the momentous importance of her discovery.

In spite of the abundant controversy surrounding global warming, the principles on which the science is based are relatively simple. They were, however, not obvious until Foote described them in a paper she presented to American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1856.

An actual greenhouse heats up because sunlight passes easily through the glass but radiated heat does not. Greenhouse gases have the same effect on a vast scale. They allow incoming energy, but block heat from radiating outward. The trapped heat warms the atmosphere.

Foote’s experiment involved filling thirty-inch glass cylinders with various gases — moist air, dry air, carbon dioxide, oxygen and hydrogen. She placed them in the sun and tracked the temperature. She found that carbon dioxide trapped much more of the sun’s energy. “An atmosphere of that gas,” she wrote, “would give to our earth a high temperature.” She was right.

But the story of Eunice Foote is not just the story of climate change. The coal-driven industrial revolution was only beginning to ramp up in her day, and the population of the earth was slightly more than one billion (it’s now eight times that). The idea that the atmosphere could be overwhelmed by greenhouse gases was purely theoretical. Since her time, fossil fuel burning has increased the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide by more than 50 percent.

Foote’s story is also one of neglect. On reading her paper, Joseph Henry, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, stated that science was “of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.”

Yet credit for the discovery of the greenhouse gas effect has long been attributed to Irish physicist John Tyndall, whose work in the field was published three years after Foote’s breakthrough. He is considered the father of climate science. Whether he knew of Foote’s work and used it without attribution is unclear.

Foote’s scientific paper, “Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun's Rays,” was the first known publication in a scientific journal by an American woman in the field of physics. She published another paper a few years later about static electricity. No woman would be credited with a similar publication for thirty-three years.

Eunice Foote was acutely aware of the obstacles in science and many other fields that faced the women of her time. She had been born in 1819 and grew up in East Bloomfield, New York, not far from the Erie Canal. The area was a center of social activism. Foote was immersed from childhood in discussions about the abolition of slavery, temperance, and women’s rights. During the 1830s she attended a pioneering school for women in Troy, New York, under the tutelage of feminist Emma Willard.

Eunice Newton (she was a distant relative of scientist Isaac Newton) married the lawyer John Foote in 1841. She was a neighbor and friend of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In 1848 Eunice attended the convention for women’s rights in nearby Seneca Falls. The conclave aimed at “the securing to woman an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions and commerce.”

It was an uphill battle. Foote worked on practical as well as theoretical questions. She patented a thermostatically controlled cook stove under her husband’s name. This was a common practice by female inventors because married women had no standing to enforce patent rights in court.

It was only a century after Foote’s death in 1888 that the world began to hear of her most important discovery. Female scholars looking at the neglected contributions of early woman scientists realized that Foote had been a pioneer in the field.

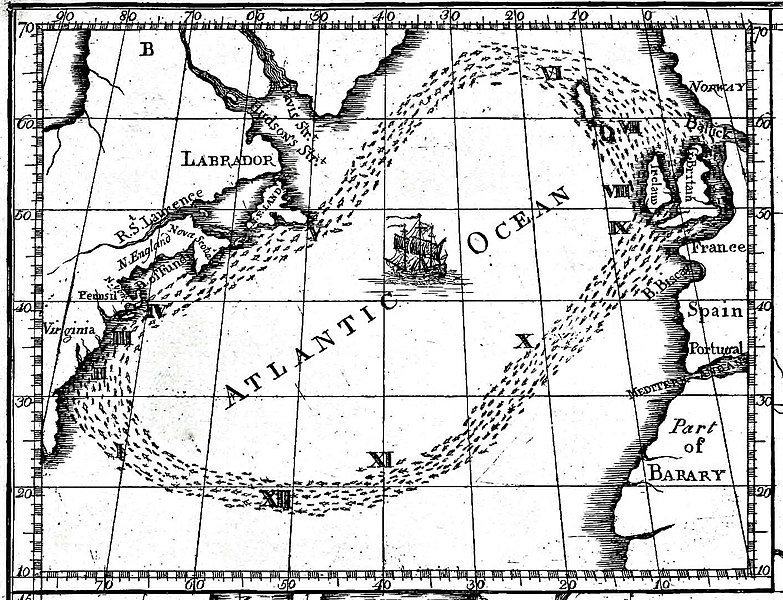

The problem that Eunice Foote speculated about in 1856 has become one of dire urgency 168 years later. One danger among many is that the effects of a warming climate will cause the massive heat-regulating ocean circulation called the Gulf Stream to collapse. Some scientists estimate that this could happen before a baby born today reaches eighth grade. The result would be a world catastrophe, the climate of northern Europe irrevocably altered, Ireland, Britain and Scandinavia plunged into famine.

Today, the secretary general of the World Meteorological Organization is a woman, Celeste Saulo, an Argentinian scientist who holds a doctorate in atmospheric sciences. “The climate crisis is THE defining challenge that humanity faces,” she has declared. It’s a fact that those who plan to vote in this year’s U.S. election might keep in mind.

Next year the Erie Canal will celebrate its bicentennial. For more on the origins of the social ferment in the region, check out my book, Heaven’s Ditch.

Thanks for continuing to bring the lost, forgotten, stolen, and suppressed stories of brilliant women to your readers!

So many warnings, so little action in response.