In January this year, fire swept through parts of Los Angeles, burning 55,000 acres and destroying more than 16,000 structures. Twenty-nine persons died. The catastrophe evoked another, earlier fire.

In one night in 1871, flames swept over Peshtigo, a lumber town fifty miles north of Green Bay, Wisconsin. The conflagration destroyed 1.3 million acres, obliterated 17 settlements, and killed as many as 2,500 men, women, and children — the exact death toll was never known. It was by far the greatest loss of life from any fire in American history. And there’s a reason you may not have heard of it.

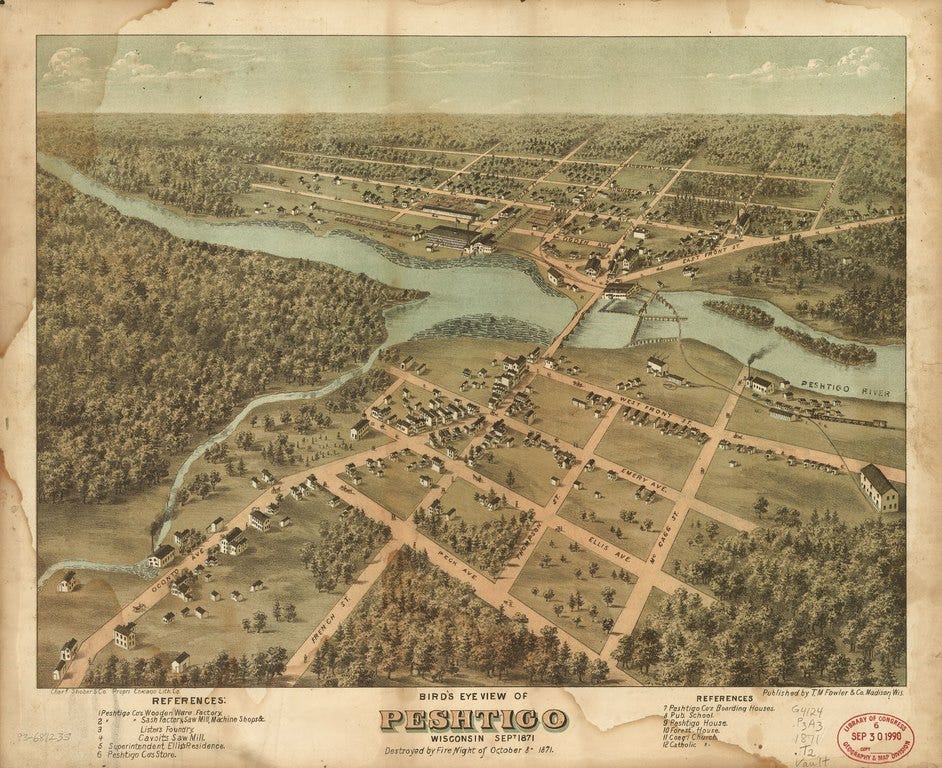

Peshtigo was a logging hub. It boasted a large sawmill and a thriving wood products factory, which turned out barrels, tubs, broom handles. Featuring two hotels and a large boarding house, the town straddled the Peshtigo River, whose water was used to float logs down from the lumber camps.

Local operators took a casual attitude toward fire. Lumberjacks piled waste branches into heaps and lit them. Farmers and railroad construction crews used a similar slash-and-burn process to clear land. They all depended on rain showers to eventually douse the coals.

But 1870 was dry, 1871 even drier. Except for a brief shower, no rain fell after July. The river dwindled and woodsmen could not get their logs to the mill. Local Menominee Indians could not paddle their canoes through marshlands to gather wild rice, a staple.

During the first week in October, the fires worsened. The sky turned yellow during the day, bright red at night. On October 7, a storm approached, bringing strong gales from the west.

For a time on the evening of October 8, a “death-like stillness hung over the doomed town,” a reporter wrote. Father Peter Pernin, priest at the local Catholic Church, said he heard “a distant roaring” approaching through the quiet darkness.

Winds suddenly mounted to hurricane force. The air in Peshtigo filled with sparks, ash, and smoke. A wall of fire hit the town. The descriptions of the inferno left by those who survived are surreal.

A “lurid glare” lit the scene and the roar “became a howl.” Roofs blew off houses. A “blazin' herd of hogs” stampeded through the street. Buildings didn’t just catch fire, they exploded into flame, one after another.

Father Pernin wrote that many of his flock imagined “that the end of the world had arrived.” He said, “the air was no longer fit for inhalation.” He saw “nothing but flames; houses, trees and the air itself were on fire.”

Some citizens began to load wagons with belongings and pets, but quickly realized they were too late. Their clothes began to burn and they ripped them off. Those who could, ran. Some crowded into the boarding house, seeking a refuge — the building burst into flames. Seventy-five panicked people burned to death

A man in the outskirts loaded his wife and five kids into a wagon and whipped the horses toward town. His family screamed that their clothes were burning, but he couldn’t stop. One of his horses fell. He tried to get the animal up. When he turned back to the wagon, he saw that his wife and all his little ones had been incinerated.

Folks headed for the river. Many groped ahead, blinded by the heat and acrid smoke. Those who reached the water found a roiling scene of horror. Corpses floated in the stream. Cattle, horses, dogs, and waterlogged sheep crowded in. A man saw a woman hanging onto the burnt tail of an ox — he grabbed her and dragged her to the bank. “She was in labor,” he remembered, “baby born in the river, never saw it.”

“Flashes of fire kept sweepin' over the water,” one witness said. The heat set victims’ hair afire and they had to duck under or drape wet clothes on their heads. Some died of hypothermia from hours in the frigid water. Many who could not swim drowned.

One young boy remembered, “My oldest brother got us children to the river, but our mother fell behind with the baby in her arms. We found them in the potato field.”

Those who survived crawled out onto the banks of the river at dawn. The aftermath showed the intensity of the fire — sand turned to glass, coins in men’s pockets liquified, a church bell turned into a puddle of molten metal. Nearly every structure in town had been destroyed. Charred bodies of loved ones lay where they had fallen, or, reduced to ashes, blew away

The Peshtigo inferno would have been big news across the country except for one thing. That same night, in a completely unrelated incident, fire took hold in Chicago, 250 miles to the south. A third of the city burned down and three hundred residents were killed. That was the headline — the Great Chicago Fire. By the time telegraph lines were reconnected to Peshtigo, the much more devastating fire there was old news.

The National Weather Service was founded in 1870, a year before the Peshtigo blaze. At the time, meteorologists lacked the resources to warn residents of the approaching inferno. This year, the government cut 20 percent of forecasting personnel from the Service, limiting the agency’s ability to respond to severe weather. Experts predict “a crisis situation” as climate change threatens ever larger blazes. Nature does not obey executive orders

Morning Jack. Fire is a terrible, terrible happening and your sister, Kate mentioned the New Jersey pine woods fire and that's why it's so hazy here, and not good to breathe. I hope this rain that's coming down hard will be helpful there. A very sad story, but needed to see. Thank you.

Again, your last line says it all. “Nature does not obey executive orders.” What a horrifying story.