The proposed appointment of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to oversee public health in the United States has raised both eyebrows and hackles. Kennedy has become famous for notions that conflict with accepted science on subjects ranging from the danger of vaccination and the cause of AIDS to the benefits of gulping raw milk.

Americans have a history of getting drunk on cocktails that mix one part science with two parts malarkey. The rage for phrenology, which took the country by storm in the nineteenth century, is a case in point.

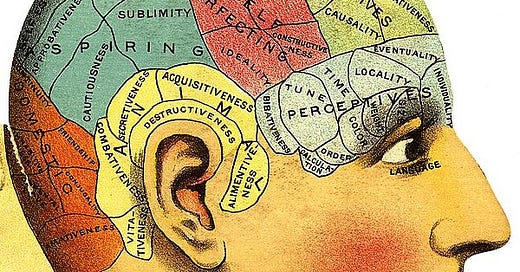

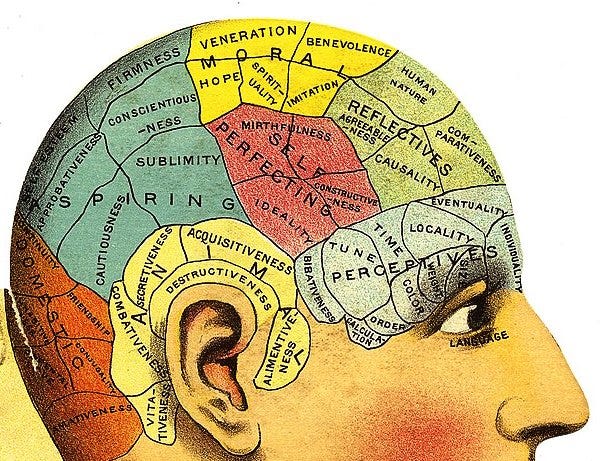

In the late 1700s, the German researcher Franz Joseph Gall proposed that the human mind was a function of the brain. A person’s character, faculties and senses were related to specific “organs” or areas within the brain. The size of these organs not only shaped personality but could be detected by the way they deformed the skull, raising small bumps.

Gall’s idea, which some proclaimed “the only true science of mind,” found fertile soil in America. Much of the interest was generated by a pair of brothers, Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, farm boys from the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York.

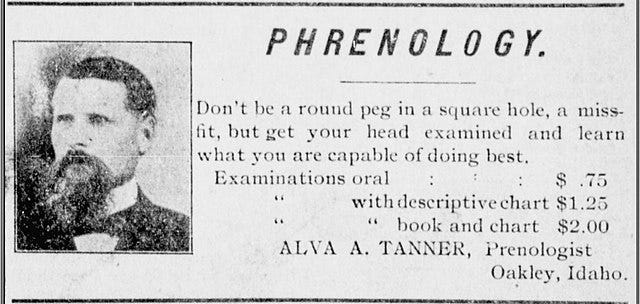

Both enrolled at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Orson attended a phrenology lecture there in 1834 and was immediately struck by the truth of the theory. Two years later, he was established in New York City, where he would “read” the bumps on a client’s skull for a fee. Lectures brought another robust revenue stream. Lorenzo followed his older brother into the profession, setting up in Philadelphia and later in England.

The Fowlers devised a phrenological bust, a ceramic model of a head with the various “faculties” mapped out. This became an essential tool for aspiring bump readers. They also collected more than a thousand human skulls from around the world, which they displayed in a museum, claiming the specimens verified the truth of phrenology.

The phenomenon had a dark side. Although the brothers were abolitionists — they considered slavery a “monstrous evil” — phrenologists routinely used the system to support the innate superiority of white Europeans. Racist and antisemitic doctrines were “proven” by the shapes of skulls.

The Fowlers’ enthusiasm veered a long way from Gall’s original premise. Their “practical” phrenology resembled a parlor game, allowing any practitioner with a smooth line of patter to make money. All he had to do was to pass his fingers over a person’s scalp, examine the Bump of Knowledge or Bump of Benevolence, and pronounce flattering judgments about the individual’s character. The operation was more Barnum than biology.

The Fowlers attracted a group of well-known clients. Walt Whitman was an enthusiast. The journalist Horace Greeley, author Ralph Waldo Emerson, and abolitionist John Brown, all sat to have their skulls read. Lorenzo Fowler examined the bumps on the head of fifteen-year-old Clara Barton and said she would never assert herself for herself, but “for others she would be fearless.” She became a nurse and founded the American Red Cross.

Mark Twain had a different experience. When the humorist visited Lorenzo anonymously, the phrenologist told him of a cavity in his skull that “represented a total absence of a ‘Sense of Humor.’” Twain returned some months later under his own identity and Lorenzo informed him that the cavity “was gone, and in its place was a Mount Everest . . . the loftiest BUMP OF HUMOR he had ever encountered.”

Orson Fowler, in his writing, organizing and lecturing went far beyond phrenology. He promoted the rights of women and opposed child labor. He advocated for vegetarianism, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, exercise, prison reform, a forty-hour work week, and sex education.

He promoted the idea of the eight-sided house, which he touted as easier to build, more efficient to heat and cool, and brighter because it accommodated more windows. A fad for octagonal structures during the1800s saw the construction of hundreds of these buildings — barns and churches as well as residences. Fowler built a four-story octagonal mansion for himself in the Hudson Valley town of Fishkill, NY, where he lived for a time

By the dawn of the twentieth century, the Fowler brothers were dead and so was phrenology. Bump reading had fallen out of fashion. But scoffers should hesitate before indulging in the last laugh. Although not a true science, phrenology paved the way for the modern understanding of the brain, both as the seat of the mind and as a complex organ in which specific areas control different functions.

Neuroscience has gone even further. The area of the brain associated with spatial perception is larger in London taxi drivers than in non-drivers, and it increases in size the longer they drive. What’s more, a detailed examination of skulls down the centuries has found an increasingly enlarged node (bump) corresponding to the brain area where language resides. Doctor Gall was most certainly on to something.

So, bartender, pour me another glass of that there raw milk. Here’s to your health!

Anyone that believes this stuff should have their head examined...

“1 part science, 2 parts malarkey” Love it, Jack. Well done.