They Were Turned Adrift: The Fate of Revolutionary War Soldiers

As we celebrate Memorial Day this weekend, it’s worth remembering a celebration that didn’t happen. It was the spring of 1783. The soldiers of the Continental Army had, after eight long years, defeated the British and guaranteed America’s independence. The Revolutionary War was over. A final gathering and gala parade were planned.

Top officers abruptly cancelled the festivities. They knew a grim truth. The soldiers, most of whom had not been paid for many months, had been promised at least three months’ pay as a first installment on what they were owed. Congress would not supply the funds to meet that paltry obligation. The men would not receive even one month's pay. Only valueless IOUs.

Their officers feared that if they released crowds of destitute armed men, the troops might resort to looting. Instead, the soldiers were sent home under the fiction of a furlough. That meant they would be subject to military discipline and potential court martial if they acted up. Once they reached their home states, they were dismissed.

It was the final insult to men who had carried the fight for so long, often short of tents, blankets and shoes. While many civilians profited from the war, the soldiers often went hungry. The men who had “suffered and bled without a murmur,” George Washington wrote, were let go “without a settlement of their accounts or a farthing of money in their pockets.”

No transportation was provided, no travel allowance. This was a particular hardship for those who had to walk home from distant theaters of war. Joseph Plumb Martin, who fought in the ranks through the entire conflict, took a job on a farm to earn enough to reach his home in Connecticut.

The land grants that recruits had been promised? Congress did hand those out. But the parcels were in remote wilderness territory. The soldiers, desperate for cash, had to sell to speculators for a few cents on the dollar.

Did the troops deserve a pension? The matter was hotly debated. On one side were the soldiers who had done the fighting, on the other, the citizens Thomas Paine called “sunshine patriots.” These folks, who had watched from the sidelines, felt that the conquest of the British was the work of all patriots, a people’s victory. No one should receive special privileges just because he had served in the army.

This idea prevailed for decades. Only those who had been disabled in the fighting received any compensation—five dollars a month. It wasn’t until the presidency of James Monroe, himself a Revolutionary War veteran, that a general pension was awarded to the boys of ‘76. The act passed in 1818, forty-three year after the war began. It offered a stipend only to soldiers who could prove they were destitute. In effect, they had to beg the government for their pensions.

The situation was personalized for me when I considered the experience of my direct ancestor, Edmund Kelly. He enlisted at the age of fourteen in a continental regiment, the Second New York. On being mustered out after the war, he was given forty acres on Seneca Lake, which was then remote Indian territory. He sold the grant to an investor.

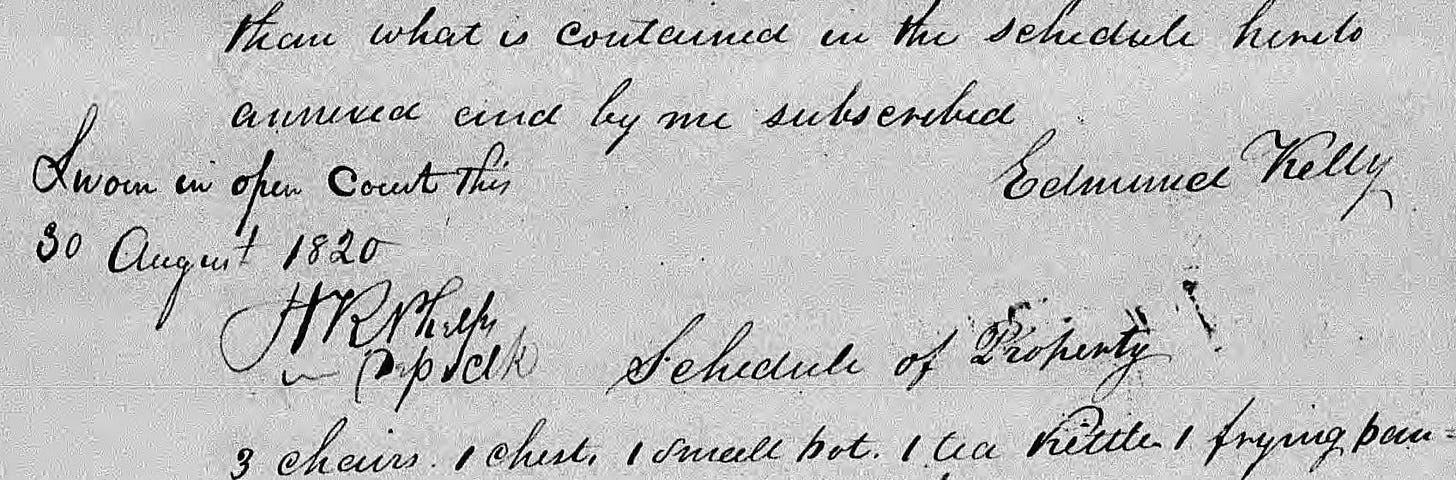

Edmund farmed until he was injured in an accident. Hard up, he applied for the 1818 pension. He had to list his assets to qualify. They included “3 chairs . . . 1 tea kettle, 1 frying pan . . . old bible and psalm book . . . 2 hens and six chickens.” He was awarded eight dollars a month.

It would be gratifying to report that all this was in the past, that Americans are now scrupulous in giving our service men and women what they deserve. Yet a recent study ordered by the Pentagon found that one in four active-duty military members is troubled by food insecurity. A substantial number of them experience actual hunger while trying to keep us safe.

Sunshine patriots today sing the praises of small government and low taxes. But war has always been expensive. And if the expense is to be shared fairly, those who take the risks and endure the trauma and lose the limbs need to be compensated.

Joseph Plumb Martin, for one, would not have been surprised. “When the country had drained the last drop of service it could screw out of the poor soldiers,” he wrote, “they were turned adrift like old worn-out horses, and nothing said about land to pasture them upon.”

Thanks to my brother Bob Kelly for his insightful research into our family’s past.

To read the stories of some of the men who fought in the Revolution, pick up a copy of my book, BAND OF GIANTS.

Seems incredible that Congress could be so callous and apparently ungrateful. Makes me wonder how we managed to win the war.

Great article Jack, just reinforces the age old dilemma of the wealthy and connected vs your everyman. I think Marx wrote about this. Still unresolved!