In the summer of 1829, one of the most bizarre trials in American history convened in the Circuit Court of the United States that covered the District of Columbia. Anne Royall, a pioneering journalist, had been indicted as a “common scold.” The case raised issues that continue to echo today. It put a spotlight on a personality that one scholar called “the most remarkable woman of her time.”

She had been born Anne Newport in 1769. Brought up on the Pennsylvania frontier, she had accompanied her widowed mother to Virginia in 1785, where they worked as servants for William Royall, a wealthy Revolutionary War veteran. At the age of eighteen, she began living with Royall as his wife — they were married ten years later. Her husband, twenty years her senior, died in 1812. She inherited his valuable plantation. His relatives contested his will and a court annulled the legacy in 1819, leaving Anne with a heap of debts.

Now fifty, Anne wanted to see some of the world. She traveled around Alabama writing perceptive letters about the newly settled territory. She got the idea of compiling these observations into a book — travel writing was popular at the time. She interviewed prominent local characters and recorded sharp commentary on daily life. Her funny, acid-tinged writing contrasted with what she called the “insipid, frothy, nauseous” prose of most women authors.

In 1824, Anne traveled to Washington, D.C., to plead for the veteran’s pension owed to her husband. She met John Quincy Adams, then secretary of state, and visited his father, former president John Adams. She was the first female journalist to interview any president. She continued to sell travel books by prepaid subscription, but struggled to make ends meet.

Royall launched blistering attacks against the evangelical religious movement that was popular at the time. Having settled in a house in Washington, she criticized a group of Presbyterians — “blackcoats” she called them — who held their services in a government-funded fire hall next door. In retaliation, they prayed silently outside her house. Sunday school children pelted her windows with rocks. She cursed them out. Charges were brought.

The trial took on a circus atmosphere. Newspapers called her an “imprudent virago.” Anne gave her adversaries nicknames like “Holy Willy,” “Miss Dina Dumpling,” and “Tom Oystertongs.” One of the judges, she wrote, “looks as though he had sat upon the rack all of his life, and lived on crab-apples.”

But the issues were serious. A form of Christian nationalism that directly challenged the U.S. Constitution was on the rise. When a preacher insisted it was “the duty of Christian freemen to elect Christian rulers,” Royall called the statement “treason from beginning to end.”

The charges were a direct attack on her freedom of speech. Yes, she had called a member of the congregation “a damned old bald headed son of a bitch.” She had also persistently exposed political corruption around the country and skewered the pretensions of self-important people. When advised that her candor might be dangerous, she retorted, “If it be dangerous to speak now, what will it be in a few years? The danger of the thing proves the necessity of it.”

Speaking out did prove dangerous for Anne as she toured the country. She broke her leg when a pious Vermonter pushed her down some porch steps. In Pittsburgh, a bookseller gashed her face with a horsewhip.

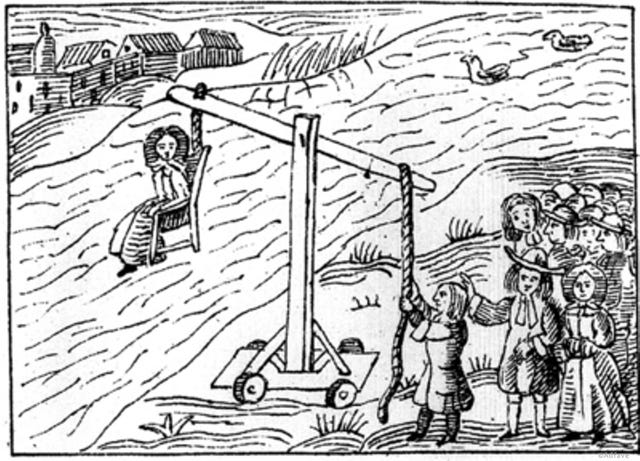

During the early 1800s, a number of other women had been tried and punished under the common-law principle of being scolds. The “crime” applied only to “troublesome and angry women.” What gave the spectacle a surreal edge was the prescribed punishment: the ducking stool. This medieval torture device consisted of a seat attached to a seesaw contraption that allowed the guilty party to be repeatedly submerged in a river. Authorities had one waiting near the courthouse.

Anne spoke at the trial against “these encroachments upon our civil and religious liberty.” The jury brought in a verdict of guilty. The judge decided to forgo the ducking and instead fined the defendant ten dollars and forced her to put up a bond to guarantee good behavior. Reporters pitched in to pay both. Anne’s reaction was: “This is a pretty country we live in.”

Anne Royall was sixty when the trial took place. The publicity helped fuel sales of her books. She spent the next quarter century writing, reporting, and publishing. She started a weekly newspaper, which she printed in her kitchen.

Anne unmasked pomposity with humor and insight. Recognizing the danger of ignorance, she pushed for greater educational opportunities. A century before women got the vote, she was zealous about their rights — “I contend that all women are like men, born free, and have equal rights.”

John Quincy Adams, who had become her friend, said she was “tolerated by some, and feared by others.” An editor noted that “she could always say something, which would set the ungodly in a roar of laughter.”

Royall kept publishing her newspaper, called The Huntress, until just before her death in 1854 at the age of eighty-five. An early biographer said her writing was “the expression of a sane, generous, and entertaining personality.” Anne herself proclaimed, “Those who have the laugh upon their side, have the victory.”

Thanks to my brother Bob for alerting me to this story.

Wow is right about Ann and staying to who she was and not letting anyone get in the way of that. Good for her!!!

What a woman!! Soul sister to you sir! xo