Of all the medals of honor given out to U.S. Marines during World War II, a third of them were awarded for a single battle on a tiny speck of land in the Pacific Ocean. Its name was Sulfur Island — in Japanese, Iwo Jima. It was a hellscape of sulfur mines, caves and barren black rock that extended north from a 550-foot-high extinct volcano called Mount Suribachi.

It was “the most heavily fortified island in the world,” a general said.

The Japanese, hidden in caverns and tunnels, held out for nearly a month against an invasion force of seventy thousand Marines. The continuous fighting was horrific, violent, and exhausting. Twenty-six thousand Marines were killed or wounded. Of the twenty thousand Japanese defenders, only two hundred were taken prisoner — the rest died.

Admiral Chester Nimitz said, “Among the Americans who served on Iwo Island, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

One of the heros who waded into that maelstrom on February 19, 1945, was Ira Hayes. He fought through the entire battle. He saw close comrades die. He endured the continual pounding of guns, rockets, mortars and bombs. At night, enemy soldiers infiltrated American positions — Ira knifed to death an attacker who had leapt into his foxhole.

Hayes emerged from obscurity by chance. Four days into the invasion, Americans had captured the peak of Suribachi and raised a small American flag. It was a tremendous morale booster. “It sure looked good,” one Marine remembered. The brass wanted a larger flag mounted so that it could be seen all over the island. Ira Hayes and several men from his unit took the flag up the mountain in the midst of the battle.

Ira found a length of iron pipe and attached the flag. He and five others hoisted the pole erect and secured it against the wind with stones. An Associated Press combat correspondent, Joe Rosenthal, snapped a photo of the event. The picture won him a Pulitzer Prize and became one of the most iconic photos of the war.

Ira Hayes fought on through the bloody campaign until the island was finally taken on March 26. He was soon ordered back to Marine Headquarters in Washington, D.C. The famous photo was to be used as an emblem for a War Bonds campaign. For several weeks, Hayes toured the country raising money for the war. He returned to the Pacific, served in the occupation of Japan, and was honorably discharged from the Marines at the end of 1945.

What distinguished Hayes from the others was the fact he was a Pima Indian. He had grown up on a reservation in Arizona. The Pima call themselves Akimel O'odham, “River People.” They subsisted along the Salt and Gila Rivers, whose flow had been choked off by dams erected to benefit white settlers.

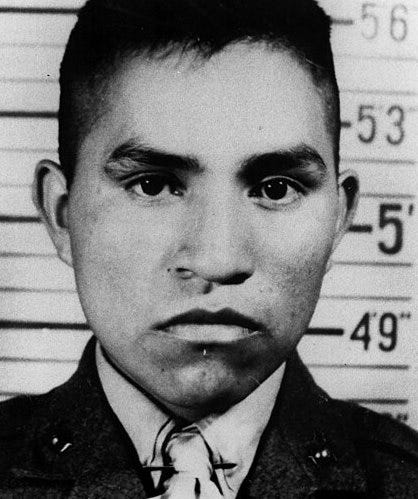

Born in 1923, Ira grew up in poverty and attended government Indian schools, where assimilation was encouraged, indigenous language and culture belittled. Friends remembered him as a shy, exceedingly quiet boy who liked to read. With the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, Ira enlisted in the Marines.

After the war, he remained a minor celebrity. “I kept getting hundreds of letters,” he said, “And people would . . . walk up to me and ask, ‘Are you the Indian who raised the flag on Iwo Jima?’” He was proud of his service, but, like many veterans, he was not inclined to talk about it with civilians.

In addition to dealing with unwanted notoriety, Hayes was haunted by the memories of his wartime experiences. Today he would perhaps be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. PTSD was little understood in the 1950s. Veterans were left to cope on their own.

“I was about to crack up thinking about all my good buddies,” Ira said. “They were better men than me and they're not coming back.” He attempted to deal with his demons by drinking. He became entangled in alcoholism and had trouble holding a job. He was arrested more than once for public intoxication.

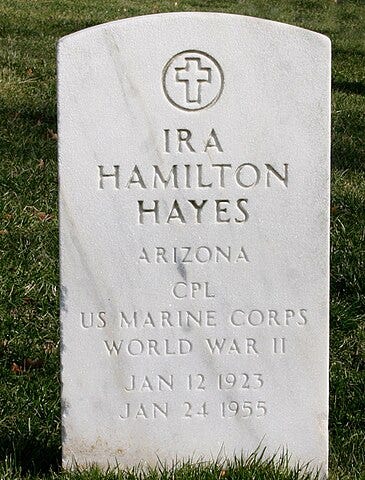

On November 10, 1954, Hayes attended the dedication of the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. He saw himself depicted in bronze, forever raising the flag. Weeks later, he was found dead from alcohol and exposure outside an adobe hut in Arizona.

Last year, more than six thousand veterans, haunted as Ira Hayes was haunted, killed themselves — seventeen every day. The government’s recent cuts to personnel at the Veterans’ Administration will throw more obstacles in the path of service men and women seeking mental health care. Similar layoffs have hampered the Veterans Crisis Line, a hotline which helps those dealing with extreme stress.

Soon after the conclusion of the battle of Iwo Jima, Rabbi Roland Gittelsohn, a Marine chaplain, gave a sermon at one of the American cemeteries on the island. “We shall not foolishly suppose,” he said, that “victory on the battlefield will automatically guarantee the triumph of democracy at home. This war has been fought by the common man; its fruits of peace must be enjoyed by the common man.” He promised that “your sons, the sons of miners and millers, the sons of farmers and workers—will inherit from your death the right to a living that is decent and secure.”

In an effort to suppress accounts of diversity in our nation’s history, the Department of Defense recently removed websites devoted to indigenous heroes, including Ira Hayes. References to women and minority veterans were also erased. Authorities later restored Hayes’s page with changes that minimized mention of his native ethnicity and culture. And so it goes.

I really dislike the fact that there even has to be wars and all the horrors that goes with it and after it and how some are treated like they don't exist. We're all human and should be treated with kindness and respect. Another good read Jack, but somewhat sad.

Another heartbreaking story that we all need to hear, thank you Jack.