What is magic? In times past, humans believed they could influence events by casting spells, mixing potions, or performing rituals. Science gave the lie to that notion — magic has been reduced to a metaphor. Today, it more often refers to a skillful show in which something that cannot possibly happen does happen. It’s the conjuror’s trick, the sleight of hand that leaves the viewer awestruck.

But if a belief in supernatural powers has faded, old prejudices remain. In the 1690s, innocent women were hanged in Salem, Massachusetts. But the image of evil remains attached to the “witches” — not to those who murdered them.

Slowly, with many setbacks, we have come to understand that women deserve equality with men, and that girls must have the right to pursue all of their dreams. So why is the world of magic dominated by men?

Adele Scarcez was born in London to Belgian parents in 1853. She learned acrobatics and dance and soon went on the stage as a trick rider in a bicycle show. She traveled to New York where she danced in early variety shows. In 1875, she married Alexander Herrmann, one of the leading magicians of the time. She helped out in his act, first as a prop handler, then as an assistant to “Herrmann the Great.”

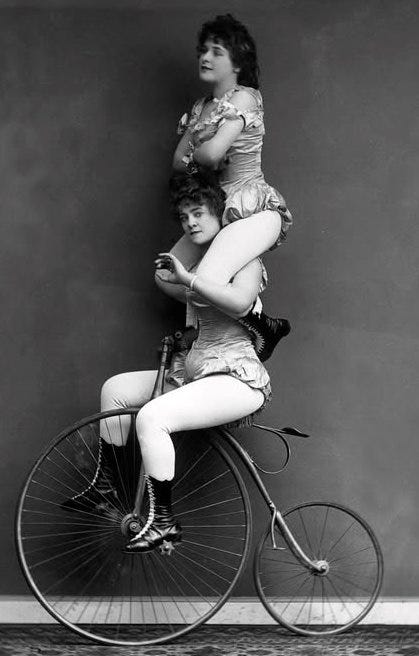

Adelaide, as she began calling herself, had an instinct for show business. She soon shared top billing with her husband. Creating what she called “spectacular magic,” she performed escape, levitation, and vanishing acts. She was fired from a gun as a human cannonball. She circled the stage on her bicycle with a girl balanced on her shoulders. She performed dance routines, disappearing into a flurry of whirling red silk that simulated flames.

Herrmann the Great dropped dead of a heart attack in 1896. Left with debts, Adelaide went on the road with a show of her own. She became world famous as the first female headline magician. “I shall not be content until I am recognized by the public as a leader in my profession,” she declared, “and entirely irrespective of the question of sex.” She succeeded and dubbed herself “The Queen of Magic.”

In one visually and emotionally stunning trick, she “hypnotized” a bride, draped her body in white silk, and made her float over the stage, passing hoops around her to show there were no wires. Adelaide then whipped the silk away — the bride had vanished. In another skit, she stumbled across the stage dressed as an old woman before diving into actual flames. She emerged as a youthful woman in a gown.

Adelaide Herrmann’s magic performances incorporated music and dance, elaborate costumes and other stagecraft. An illusion she called “Noah’s Ark” began with an empty “ark” open on stage. She closed the vessel and poured buckets of water down the chimney (the flood). Then two cats emerged from the same chimney. Then a parade of animals appeared, marching down the gangplank — dogs dressed as leopards, elephants, and zebras. Then, white doves flew out. Finally, she flung the previously empty ship open to reveal a woman lounging on a divan.

Adelaide became famous for the “bullet-catching trick,” which she learned from her late husband. She was the only woman to perform this dangerous feat. On the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, Adelaide faced a squad of six militiamen. Each loaded his rifle with a marked bullet. She held a plate in front of her chest. They fired at her simultaneously. She staggered, then revealed the same six bullets lying on the plate.

What was remarkable about Adelaide was her longevity. She remained a top act in vaudeville houses into her seventies. In 1926, a warehouse fire destroyed her props and killed most of the dogs from her act. Even that didn’t stop her — she carried on with a smaller show for two more years. She died in 1932 at the age of seventy-nine.

A century later, Adelaide remains virtually unknown compared to male performers of the era like Harry Houdini. Today, fewer than one in ten professional magicians are women. Why does it matter? First, because there are girls out there who may have the talent to become superstars. Lacking role models and opportunity, they never fulfill their potential. But also because inequality denies us all of the delight of being entertained by the most superb illusionists.

“We cannot be what we cannot dream,” the novelist Richard Flanagan wrote. Gabriella Lester, a young magician working today, was quoted in The New York Times, saying she strove to “create that person that I would have wanted my younger self to see and be like, ‘She’s cool. That’s what I want to do.’” God knows we need more magic in the world.

Wow, she must have been a magician to get that woman balanced on her shoulders and ride that bike. Great read Jack.

Jack, you tell us about people we couldn't imagine in our wildest dreams, thank you