Most of us, when we look back on our lives, remember certain events with regret. We might admit our mistakes, but it’s harder to say, “I'm sorry,” to those we’ve wronged. In 1957, two young people were swept up in history. The incident would stay with each of them all their lives.

Three years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that “separate but equal” schools were neither fair nor legal. Segregation would have to end. Southern states resisted implementing the order.

As schools opened in September 1957, attempts by African American students to go to school in the South met mob violence. President Eisenhower had to send in soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division to enforce the law in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In Charlotte, North Carolina, a different drama played out. State educators had decided to begin integration by admitting four African American students to four different schools. Dorothy Counts was chosen to go to all-white Harding High.

Dorothy — everyone called her Dot except her father — had grown up in a large extended family. She loved to visit her grandmother, Emily, a seamstress in a tiny town on the South Carolina border. Every summer, Emily sewed her a new dress for school. In 1957, it was a colorful red and yellow plaid frock, set off by a bright-yellow bow.

At fifteen, tall for her age, Dot was entering her sophomore year. She looked forward to a better educational experience than she had received in the segregated, underfunded schools she had always attended. Her father, Herman, taught theology at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte. He wanted the best for his daughter and her three brothers.

White Citizens’ Councils had been organized throughout the South to fight segregation. They planned a rally to protest Dorothy Counts’ admission. On September 4, Council members and as many as four hundred students gathered outside the school.

Dorothy’s father drove her to school that day. He took along a friend, Edwin Thompkins, who offered to accompany Dot to the building while her father parked the car.

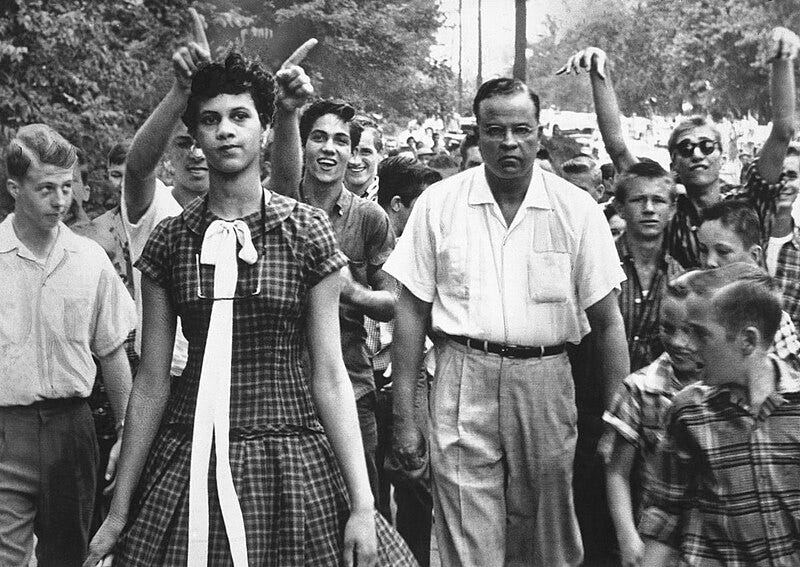

To get to the school entrance, Dot had to walk through the crowd. Students and protestors formed a solid wall across her path, but when she approached, they gave way. Then they followed her. They jeered. They shouted racial slurs. The wife of a White Citizens’ Council officer screamed, “Spit on her, girls, spit on her!” Their spit was soon dripping from the dress her grandmother had made.

“All we knew was that she was different from us,” one participant remembered later, “and we didn't want her there.”

A photo of the incident by Douglas Martin won the 1957 World Press Photo of the Year prize. When the expatriate writer James Baldwin saw the picture in a Paris newspaper, he declared: “There was unutterable pride, tension and anguish in that girl’s face as she approached the halls of learning, with history jeering at her back. It made me furious and filled me with both hatred and pity and it made me ashamed.”

Although mostly hidden in the crowd, one of the faces in that photograph belonged to William “Woody” Cooper, the son of a Charlotte policeman. Woody didn't join the jeering and name-calling. He simply watched.

Dorothy Counts attended Harding High for less than a week. Each day her father asked if she wanted to go back. At first she said yes. After fellow students gathered in the cafeteria to spit on her lunch, after she was struck by thrown erasers, and after teachers ignored her in class, she decided it was too dangerous to continue. Her parents sent her to live with relatives outside Philadelphia. She attended a private school and later graduated from Johnson C. Smith University.

Before the incident, Dorothy had wanted to be a nurse. She decided instead to devote her life to helping underprivileged children. She wanted to “make sure no child ever goes through what I went through.” She worked as a childcare services administrator and started a mentoring program.

Woody Cooper went on to a career in computer software. He married a girl he had dated at Harding. He couldn't get the photo out of his mind. It worried him for fifty years. One day he heard a Sunday school teacher talk about sins of omission — not doing the wrong thing, but failing to do the right. Remembering the incident in 1957, he said, “I thought to myself why didn’t you at least say something?”

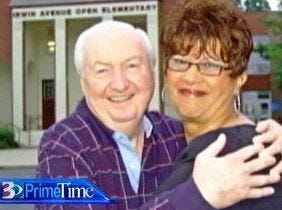

In 2006, Cooper emailed a reporter who had written a story about Counts. The reporter passed on the message to Dot, who now went by her married name Counts-Scoggins. Woody wanted to say he was sorry. It was the first time anyone in that picture had contacted Dot. She and Woody met in a Charlotte restaurant and he asked for forgiveness. “I forgave you a long time ago,” Dot told him.

Dot and Woody became friends. He sat in the front row of Harding High auditorium when the Class of 2008 honored her with the diploma she had not received fifty years earlier. Two years later, Woody was stricken with cancer and entered a hospice facility. Dot came and sat with him for two hours and kissed him on the forehead. He died the next day

OMG What a beautiful, touching story!

Thank you very much, Jack

Thank you again Jack for this read. It made my heart sad as to how badly we treated this young lady of color. In some states, it's still the same old crap, and pray that someday, it will different.