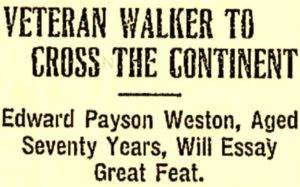

On March 15, 1909, Edward Payson Weston left City Hall in New York City at four in the afternoon to take a walk. His destination was San Francisco. He planned to become the first person to walk across the United States. He vowed to do it in a hundred days. The date was significant. It was his 70th birthday.

Walking was popular in the 1800s. Henry David Thoreau hit the road regularly to preserve his “health and spirits.” The composer Tchaikovsky walked for two hours daily without fail. “Above all, do not lose your desire to walk,”philosopher Søren Kierkegaard advised. “Every day, I walk myself into a state of well-being.”

In his younger days, Weston had helped turn walking into a popular spectator sport. It all began in 1860, when he was nineteen. Weston told a friend that if Lincoln won the presidency, he would walk from Boston to Washington to view the inauguration. He proved true to his word, setting out in March 1861 at a brisk pace with a couple of friends accompanying him in a carriage to verify that he had walked the entire 478 miles.

Along the route, he handed out flyers for sponsors like Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Co. to defray expenses. In Framingham, Massachusetts, he was kissed by a “bevy” of women, who asked him to pass on the smooches to President Lincoln. Weston got to Washington in a little more than ten days — the publicity yielded an invitation to the White House, where he shook Lincoln’s hand.

After the Civil War, walking long distances became a fad. Six-day races were particularly popular — Weston collected prize money while out-walking most of the competition. In 1867, he walked from Portland, Maine, to Chicago, twelve hundred miles. He covered forty-six miles every day and won a $10,000 prize (more than $200,000 in today’s currency).

Pedestrianism, as it was called, faded later in the century. First the bicycle, then the motorcar became the arbiters of speed for racing or simply getting around. Walking was old hat.

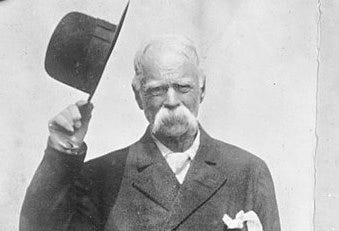

But in 1909, extreme walkers still attracted crowds of spectators. The Nation described his long walk as “an effective protest against the present-day craving for speed and locomotion.” Weston was living proof that age did not inevitably lead to decrepitude. “I always said that walking would keep a man young,” he declared.

Heading out on his cross-country trek, Weston walked from New York City to Albany before heading west. He was going great guns when he reached Chicago on April 17. He had completed a quarter of the distance and was a hundred miles ahead of his schedule. Slender, with a drooping white mustache, he moved along “with the zest of a boy.”

His habit was to walk six days a week — he always reserved Sunday as a rest day and didn’t count those days in the hundred-day goal. He would cover as much as 72 miles in a day. “The worst of my trip is now over,” he said.

In fact, the worst was yet to come. Spring weather meant frequent rain storms, which turned the dirt roads of the day to mud. In the West, he took to walking along railroad tracks. The prevailing westerly winds slowed him considerably.

The motor car that was accompanying him to track his progress and carry supplies got stuck more than once and then broke down. As he moved onto the plains, there were fewer towns, fewer spectators. He had a hard time obtaining the milk and eggs that were his main sustenance.

Then came the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming, the deserts of Nevada, and the Sierra Nevada range in California. It was clear he would not be able to make the coast by his deadline. He walked into San Francisco on July 14, five days after his goal had passed. He had covered 3,935 miles in 105 days, an average of 37.5 miles every day.

Having failed to meet his own expectations, Weston proclaimed the effort a “wretched failure.”

But he wasn’t done. The following year, he set out again, this time starting from Los Angeles. He headed east along a southern route. With better weather, he averaged more than 45 miles a day. In spite of side trips to the Grand Canyon and the Petrified Forest, he arrived in New York 78 days later. An estimated half-million New Yorkers turned out to welcome him.

He announced that this would be his last long walk. In spite of his retirement, he took a stroll from New York to Minneapolis in 1913. But in 1927, while he was walking to church, the future caught up with him. He was struck by a New York City taxicab, an accident that left him in a wheelchair. He died two years later at the age of ninety. He claimed to have walked 90,000 miles in his life.

Edward Weston was considered by many an oddball. In fact, he was attuned to the thousands of years of evolution that have defined humans as walking animals. Modern science has confirmed common sense: We were made to walk.

“I have been walking all my life and expect to continue walking until I drop,” Weston declared when he had completed his cross-country trek. “I must keep on the move.”

Fascinating. Thanks, Jack. I think I'll take a stroll in Poet's Walk.

I've always been and crawling enthusiast. Gotta have really good knee pads, though