I have only seen one president in the flesh — I glimpsed Lyndon Johnson riding along a street in New York on his way to Bobby Kennedy’s funeral in 1968. There he was — waving to passers-by through the bulletproof glass of his limousine.

Movies show politicians back to William McKinley in the 1890s. Photographs cover our chief executives as far as the1840s, when President Polk led us into the Mexican War. For historical figures from earlier times — George Washington, Napoleon, Bach or the Buddha — we have to rely on paintings, busts and engravings.

Gaining a perspective on time is essential for navigating history. Some college students, I’m told, do not know in which century the Civil War took place (or who won). So, perhaps it’s a good idea to give our temporal imaginations an occasional stretch.

If we imagine the reign of the first Pharaoh of Egypt, a fellow whose nickname was “The Fierce Catfish,” we’re going back to around 3,000 BC, when civilization still had its training wheels on. But the 5,000 years from Catfish to Trump is far less than the 45,000 years since modern humans occupied Europe and left their handprints on the walls of caves. And members of the homo sapiens club — “wise men,” or perhaps “wise guys” — had already been twiddling their opposable thumbs for 270,000 years at that point. Two hundred and seventy millennia.

Although we’ve all seen Fred Flintstone riding a brontosaurus, scientists estimate that dinosaurs had been extinct for a whopping 63 million years before the caveman era arrived. Before T-Rex, much of the earth was a hot, swampy forest populated by three-foot-long salamanders and dragon flies the size of eagles.

If we imagine the entire 4.5-billion-year span of the earth’s existence as a single year and ourselves at midnight on the last day, then the dinosaurs checked out the day after Christmas after running things for two weeks. Humans were still nowhere to be seen at sunrise on December 31. They came down from the trees about 11:30 p.m. on New Year’s Eve. All of civilization has unfolded in the last minute before the dropping of the ball.

Mark Twain proposed a different comparison. “If the Eiffel Tower were now representing the world’s age,” he wrote in 1903, “the skin of paint on the pinnacle-knob at its summit would represent man’s share of that age.”

Welcome to the world of “deep time.” That term was coined by writer John McPhee in an essay about American geology in 1981. The idea has been around since the eighteenth century.

In 1795, Scottish scientist James Hutton, known as the father of geology, published his Theory of the Earth. The core of Hutton’s notion was that geological change was gradual and largely uniform. The processes we see on earth today — erosion, sedimentation, glaciers — are what have always shaped the earth. To do so, they needed time. A lot of time.

One of Hutton’s colleagues remarked: “The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far back into the abyss of time.” And it still does. Our imaginations are trained to pay attention to human-scale time. It’ll be a year until I graduate — or retire. The kids grow up so fast. Waiter, what’s keeping that fried catfish I ordered?

It’s natural for humans to imagine a human-centered world. Knowing that we are only a recent and temporary manifestation of nature is, to say the least, humbling. But the changes imposed on the earth’s climate by our collective behavior might suggest that we, or future generations, could profit from a longer-term perspective.

We know now that humans occupy a tiny flash of time and a tiny speck of a very broad universe. Does that render us insignificant and, as a result, meaningless?

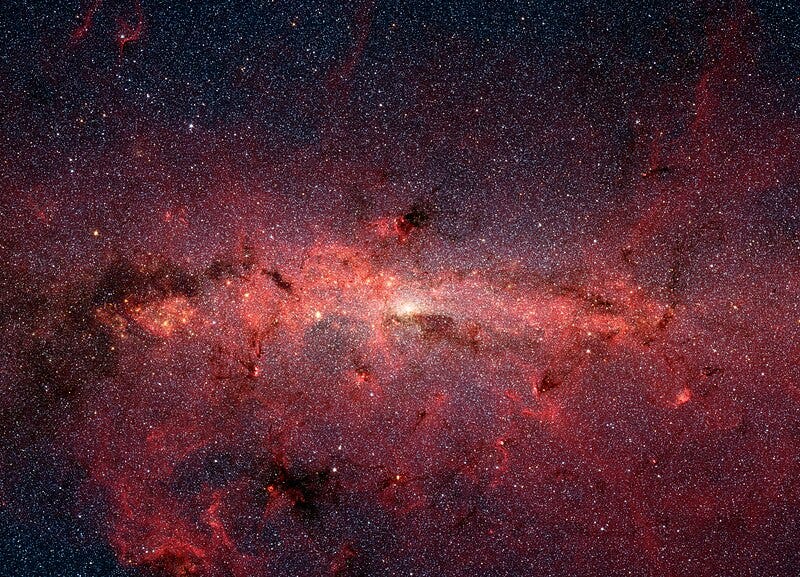

Perhaps just the opposite. As far as we know, we’re the only creatures in our galaxy, maybe in the entire universe, with the knowledge of that universe’s vastness. Science has given us tools to expand our concepts of time and space to their true proportions. We may be the only means by which the universe can reflect on itself, know itself, and wonder at itself.

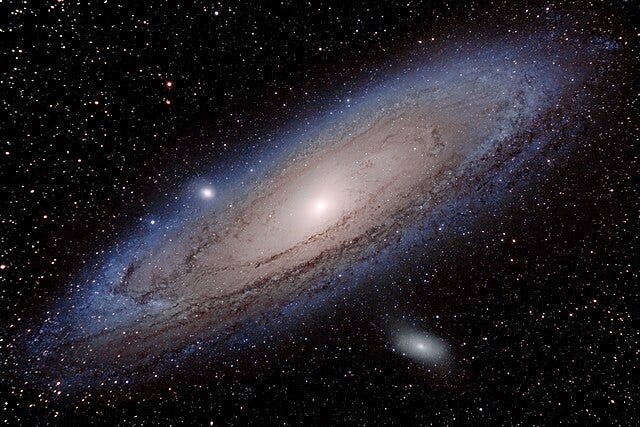

Science has not shown us everything yet. But the intricacy of life, as revealed by the tools of science, is profound. Think about the way DNA molecules determine the details of the life of a fruit fly — or of our own lives. Or take a gander at the Andromeda Galaxy and reflect on the awe-inspiring scope of the stars and distant worlds.

Will we learn to treasure our unique perspective? In time, perhaps. Will we follow the dinosaurs to extinction? Inevitably, yes. But we must leave the implications of those questions to philosophers. We can only trust that we are, in fact, far from insignificant. That, as Joni Mitchell pointed out, “We are stardust. We are golden.” All we can do is to use the time we have on earth wisely.

Holy Cow, Jack! I love this perspective, both your facts and your jokes. This made my day something other than depressing.

I remember that day with the LBJ drive-by. Your brother Bob and I were there to pick you up from Columbia and drive you home. You were fresh off some massive protests by the SDS. Fun times. I wish today's generation would wake up and storm Washington DC but their to busy looking at their phones. As for your article, it has sent me reeling back into the Existential Void!